REVIEW: Loss at Luminato Festival/Theatre Centre

“My story, like my blood, starts with my family.”

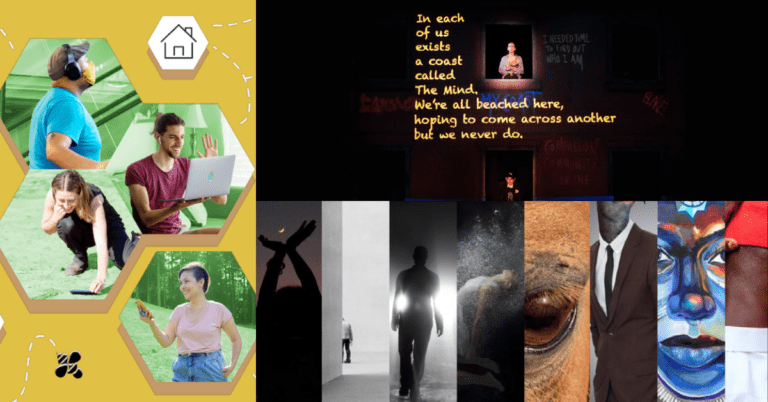

Ian Kamau paints a moving portrait of his family’s history of sadness and grief with Loss, produced by the Theatre Centre and presented by the Luminato Festival.

Loss is not a play and creator/writer/performer Kamau is clear about this from the beginning. It’s a collection of stories — his stories and his family’s stories. It’s his life, yet it’s a “performance, a simulacra, like a copy or a mirror,” Kamau tells us at the top of the show.

In truth, watching Loss feels less like seeing a “show” and more like experiencing a poem performed. The text seems like something the author has to express one way or another, and while it is intended that someone be the recipient of the work, an audience might not be wholly necessary. Kamau even states in his creator’s notes that he was “more interested in the personal process than [Loss’s] presentation,” which is probably the best lens through which to view the show.

The first story Kamau shares is that of the deep depression he experienced more than ten years ago. Sitting at a music stand with a handheld microphone, he tells us how he understood then what others might feel when they say they don’t want to live. From there, he creates a thread through his memories and his family’s stories of grief, centring often on his paternal grandmother, Nora, and her death back when his father (co-writer Roger McTair) was only ten years old. It may be more accurate to say the focus is on the difficulty in getting Kamau’s family to open up about her death or, at the very least, her life.

In between those stories, Kamau shares other memories, both sad and not sad, poems by McTair, and a few short passages on mythologies and folklore about strong emotions. We listen to Kamau wade through his life, the things he’s seen, and the lives of those who came before to try and find the roots of his sadness.

Despite the personal and vulnerable nature of the content, Kamau speaks at an even, detached tone, allowing the text and the production elements to do the emotional heavy lifting.

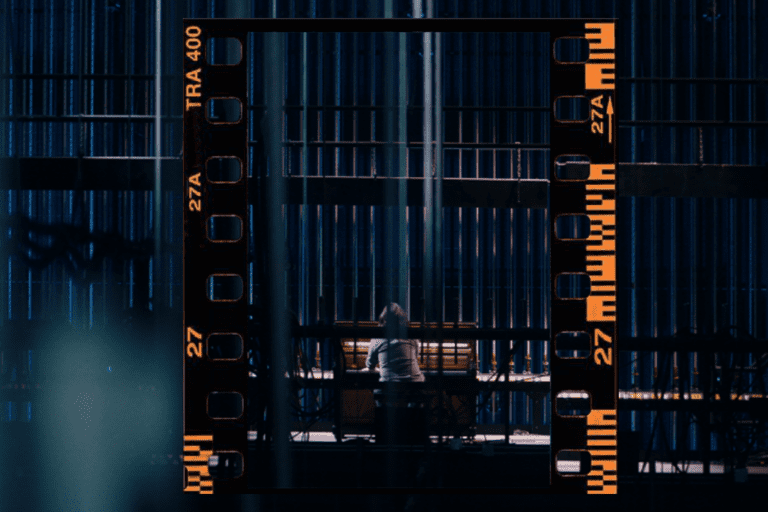

The stage (a square section of the floor in the Harbourfront Centre Theatre’s black box marked in white) is set up in the round, with a circle of audience members right behind Kamau and live musicians (composer and music director Bruce A. Russell on piano and synth, Dennis Passley on tenor saxophone, and Dyheim Stewart on guitar) who play through almost the entirety of the show. Further back, the audience sits on risers at opposing ends of the space or in narrow balconies lining two of the walls. Above each riser is a projector screen, where my eyes stayed for most of the show. Footage of home and family (filmmaker Tiffany Hsiung, video designer Jeremy Mimnagh, and contributing videographer Ty Harper) supports Kamau’s stories, giving a clearer and more intimate picture of the setting.

There is a certain lack of structure to Loss, as the stories are not presented chronologically. The pace is almost meditative throughout the 90-minute run time (save for a particularly intense sequence on the loss of Black lives at the hands of the police). The effect is that of a stream of consciousness emphasizing the personal process angle of the dramaturgy; it feels as though Kamau has strung together the stories with emotional association as if written in the order they came to him in a train of thought.

The fact that I was there, was moved by the stories, and am now writing about them feels inconsequential. Kamau, with the help of a residency at the Theatre Centre, wrote a show with his father that gets to the heart of a familial pain and by doing so seemingly resolves a greater turmoil within himself. With that, Loss has done all it really needed to do and it was touching to witness.

Loss closed on June 18. You can learn more about the production here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments