REVIEW: Lighthouse Theatre brings haunting edge to Mary’s Wedding

When I walked the main street of Port Dover ahead of the opening of Mary Wedding’s, happy beachgoers dawdling around me, there was no way I could have predicted that I would be desperately stifling tears in a public washroom just mere hours later.

Indeed, the Lighthouse Festival’s production of Stephen Massicotte’s historical romance is an emotional heavy hitter, swinging between endearing meet-cutes and gut-wrenching loss and leaving a chorus of sniffles and whimpers bouncing off of the more than 100-year-old walls.

Set between 1914 and 1920 in the dream of the titular Mary (played by Evelyn Wiebe) before her titular wedding, we follow her subconscious through dreams of her and her love, the “dirty farm boy” Charlie (played by Daniel Reale). We meet Mary and Charlie in a barn where she soothes his fear of an ongoing thunderstorm with poetry (reciting Alfred Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade”), weaving then through their secret courting under the eye of Mary’s domineering but never-seen mother, to Charlie’s service as a Canadian trooper in the First World War. However, as dreams do, the plot veers into non-linearity as Mary’s fears and her knowledge of the future bleed into the fabric of her memories.

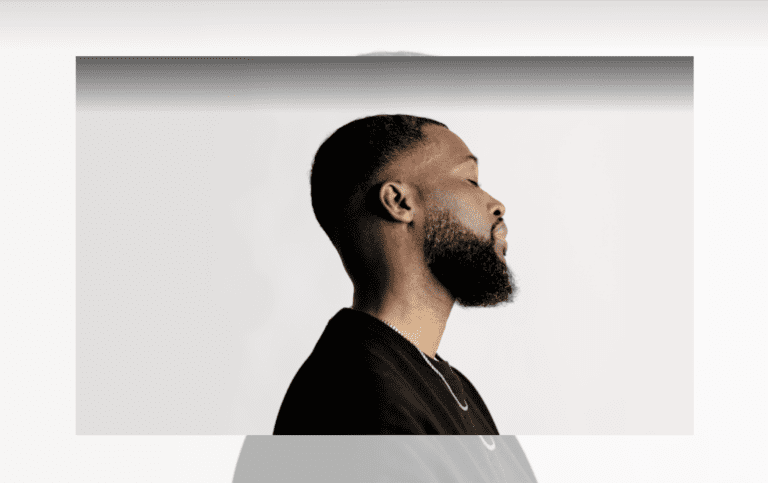

Despite jumping quickly between the years, Reale and Wiebe aptly execute the switches from hopeful, innocent kids in love to the worn, aged demeanor of veterans and those who grieve them. The performances complement the text itself, which juxtaposes Massicotte’s prose against Tennyson’s poems. Where Tennyson’s words present romanticized versions of war and heartache (Mary raves about “The Lady of Shalott”), Massicotte poetically dismantles the naive visions of life the characters get from Tennyson. Charlie never looks more boyish than when he excitedly tells Mary his plans to enlist and fight like in The Charge of the Light Brigade to then — not more than 10 minutes later (or earlier?) — be holding the dying body of his sergeant (also played by Wiebe, keeping her involved in war scenes and lending a visual reference for the way Charlie sees Mary in everything, everywhere which is a favoured expression in the text for love and grief).

Derek Ritschel’s direction allows for a lot of pauses and breathing room that emphasizes the slow, dreamy quality of key emotional moments. At some points, however, I found the energy jumped too fast. When I attended, other audience members and I startled in our seats more than once. Within the first few minutes of Mary’s appearance on stage, she yells at Charlie in a manner akin to the precog Agatha screaming at Tom Cruise to run in Minority Report. Such unsettling moments can have their purpose, but it wasn’t always clear to me what that purpose was. I would have said the show had reached a climax too soon if not for Wiebe’s absolutely heartbreaking performance in her final memories with Charlie, sparking the aforementioned weeping.

Alex Amini’s modest costume design helps the performances remain free from distractions; frequent changes might have imposed on actors needing to travel through time and space. Mary wears a plain white nightgown even when standing in for Charlie’s sergeant, while Charlie wears high-waisted trousers with suspenders over a white shirt. The only change in costume happens when Charlie repeatedly swaps between jacket or and no-jacket to indicate before the war and during.

A quick Google Image search will tell you this is not a particularly unique design for the play, but there are still small details that emphasize youth when necessary (like Mary’s high neckline and long sleeves) and possess a utilitarian quality for time-jumping (like Charlie’s leg wraps) which differentiate Amini’s take on the characters’ looks.

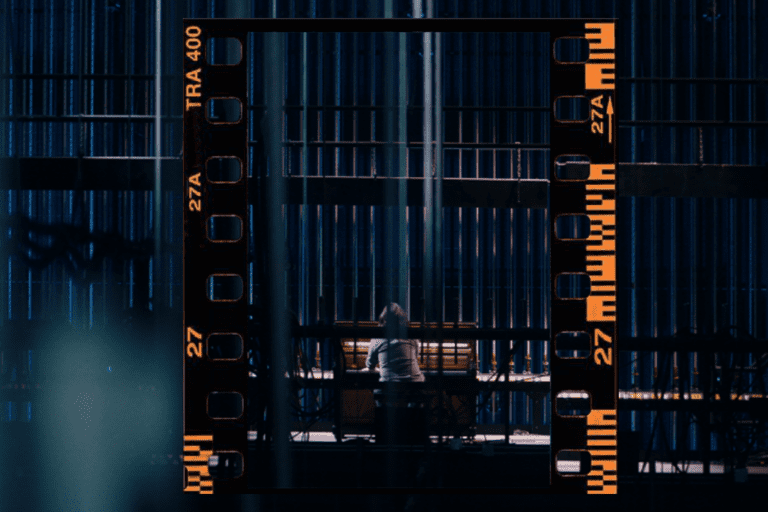

William Chesney’s set design, a collection of tilted platforms and wooden support beams encapsulating Mary’s home and the inside of an old barn, has a similar multipurpose nature that provides a nice physical playground for action. Shorter wooden supports downstage function as the railing of an ocean liner, as horses’ tethers, and even as horses for the actors to mount and ride. The design does seem to miss one opportunity in embracing a blended, surreal look that embodies both home and overseas. The set, though minimal, remains firmly rooted in the Canadian homestead opting more to be ignored during war scenes.

While I’ve called Mary’s Wedding a romance, as I find Mary and Charlie’s connection to be the best part and what makes the ending so powerful (along with Wiebe’s performance), Massicotte’s use of real Canadian military history grounds the story and elevates the genre. Charlie’s sergeant is based on a real Canadian soldier, Gordon Flowerdew, who led the real-life charge we see portrayed and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. The Lighthouse Festival has included a write-up on Flowerdew in the lobby and the program, helping the audience picture the characters in the real world.

Mary and Charlie may be fictional characters and their story dramatically enhanced but there is no doubt countless others have experienced and are experiencing similar tragedies. Just as Mary soothes Charlie with a meditative use of poetry, Mary’s Wedding ends on a moving mantra for the grief-stricken. Mary and Charlie tell us it’s okay to remember those you loved in the past and it’s okay to remember them a little less as you make more memories in the present. If you, like me, enjoy touching tales of love and loss, then you’ll be happy you saw Mary’s Wedding, even if you leave in tears.

You can learn more about Mary’s Wedding here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments