REVIEW: Neptune’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead delights in dichotomy

Take a beloved contemporary play by Tom Stoppard, cast starring actors from the Lord of the Rings films, and finish it off with some of Canadian theatre’s best Shakespearean actors, and you’ve got an assured box office hit. But star power isn’t the only reason Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead shines — instead, it’s the clever use of contrast between the large and small that lights up the stage, and these contrasts extend through every aspect of the production. Director Jeremy Webb’s vision is clear throughout the play, and utilizes the complex demands of the script to craft a dance between elements of decadence and distress.

The play’s premise is simple, yet opens a world of possibility: it’s Hamlet, told from the perspective of the ill-fated Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Tom Stoppard’s famed 1966 script weaves in and out of Shakespeare’s familiar text while filling the audience in on what “R and G” are up to when they aren’t on stage. For the most part. that’s trying to figure out what the heck is going on with that tricky Prince of Denmark, a task made a little harder when they can’t even seem to remember how they ended up here in the first place.

Even if you’re not familiar with Hamlet, the title provides you with the key information: These guys are going to die. The play is about the journey.

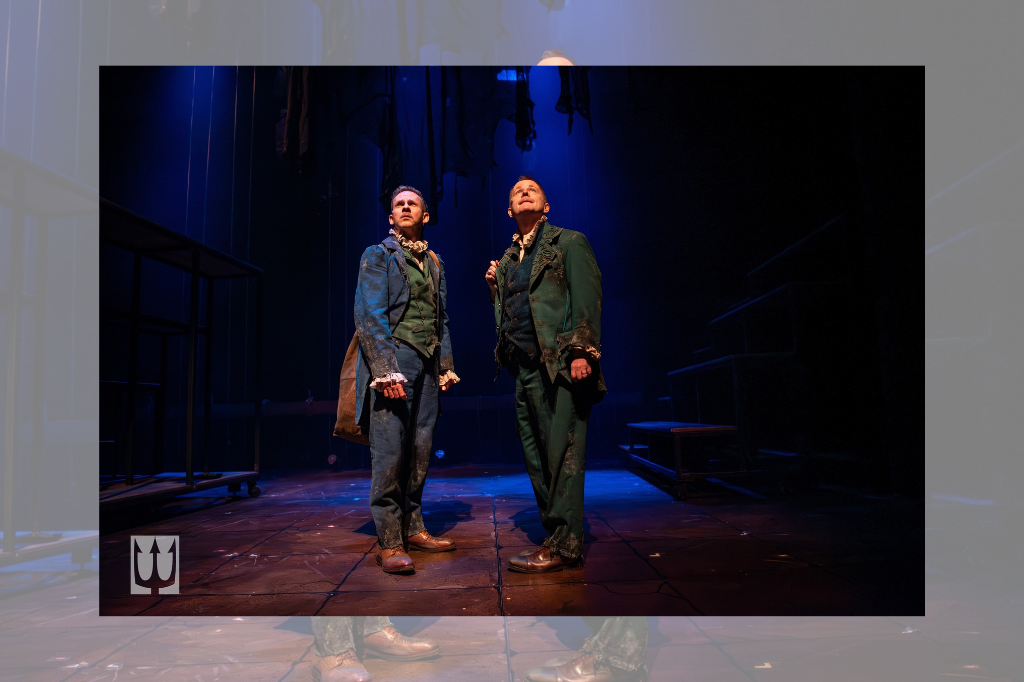

The show opens with Rosencrantz (Dominic Monaghan) and Guildenstern (Billy Boyd) in complementary blue and green suits that seem just a little ragged, alone on a stage decorated to be… well, a stage, albeit an abandoned one. The two sit on a set of sparse metal risers, while tattered curtains hang haphazardly behind them, in shadowy light that leads us into the metafictional world of this play, where reality and performance blend together.

Immediately, contrasts are at play: Boyd’s Guildenstern is thoughtful, chatty, usually talking himself in circles, while Monaghan’s Rosencrantz punctuates his ramblings with occasional insights and physical comedy. Boyd and Monaghan play off each other like old friends — their characters have clearly known each other for as long as they remember (even though they seem to have forgotten when that was). Their dialogue is snappy and almost dizzying, both to the audience and themselves, but the confusion of the characters is the comedy, in true absurdist fashion. The inherent appeal of this production is in this dynamic. Webb captures the comedic pace of Boyd and Monaghan that is familiar to fans of the celebrity duo, but utilizes that pace to pull the less theatre-minded easily into the absurdism of the script.

The mid-stage curtain then rises to reveal a troupe of actors who call themselves the Tragedians, led by Michael Blake as The Player. Blake perfectly complements the leading duo — he slides easily into the scene, matching Guildenstern’s snappy dialogue with his own witty rhetoric, and Rosencrantz’s large physical movement with bold, extravagant movement. The players begin to further blur the borders between reality and representation as some of them transform into characters from Hamlet, and the more familiar plot begins to unfold. Pasha Ebrahimi as Hamlet is an intense inferno, ferocious and assured and grounded, the starkest contrast to the shadowy uncertainty of our titular characters as they try to puzzle out what exactly is going on around them.

The scenes with the rest of the cast feel incredibly decadent, with the company of 11 actors in layers and layers of fabric and masks gesticulating dramatically in the light. At first, this felt strange to me; why are there so many people on stage? Such a large cast feels almost jarring against the simpler scenes where Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are alone, but Webb’s choice for a large cast is not simply to have bodies in the space. As the play continues, the high energy of the full company scenes allow for the quieter, introspective moments of the piece to feel all the more poignant, as the two contemplate their existence, reality, life, and death.

Webb continues to build contrasts between the simple and the extreme through the rest of the production’s aesthetic. Kaelen MacDonald’s costumes, built from shining fabrics, are shape-shifters — under certain lighting they seem glorious and indulgent, while in others they seem to show wear, dirt, and grime. The sound design by Deanna H. Choi swings wildly between comedically hollow echoes of certain lines, to a more subtle reverb to demonstrate scale as the Hamlet characters declaim their iconic lines. Andrew Cull’s set moves constantly, creating everything from an actual theatre to a moving ship, all from what seems like fragments of a theatre that has fallen into shambles.

The play showcases many such contrasting beats and design elements, to great emotional effect. It is heart-racing when the story moves into the familiar world of Hamlet, and then heart-wrenching as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern come closer and closer to their inevitable fates, and whatever may come after. The result is the ride of a lifetime, so strap in and hold onto your hats.

Neptune Theatre’s production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead runs until February 25 in Halifax, before moving to Mirvish Productions from March 5 to 31. You can learn more about the production here (Halifax) and here (Toronto).

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here and here.

Comments