REVIEW: Rubble at Theatre Passe Muraille/Aluna Theatre

You have fifty-eight seconds to get out of your house.

Fifty-seven.

Fifty-six.

Even without an ominous countdown, life on the Gaza Strip is tense at the best of times. It’s the third-most densely populated political unit in the world, a highly contested stretch of land on the Mediterranean Sea. A life in Gaza is one of unpredictability, scarcity, fear. Everything from grocery shopping to studying for an exam comes with the highest possible stakes.

Gaza has served as the setting for any number of plays, including Cary Churchill’s controversial Seven Jewish Children and Alan Rickman and Katharine Viner’s documentary project My Name Is Rachel Corrie. In Rubble, Theatre Passe Muraille and Aluna Theatre’s hard-hitting, meticulous exploration of family life in Gaza seconds before a fatal explosion, we see the true cost of Middle Eastern violence play out in real time, set to the hypnotic cadence of Lena Khalaf Tuffaha and Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry.

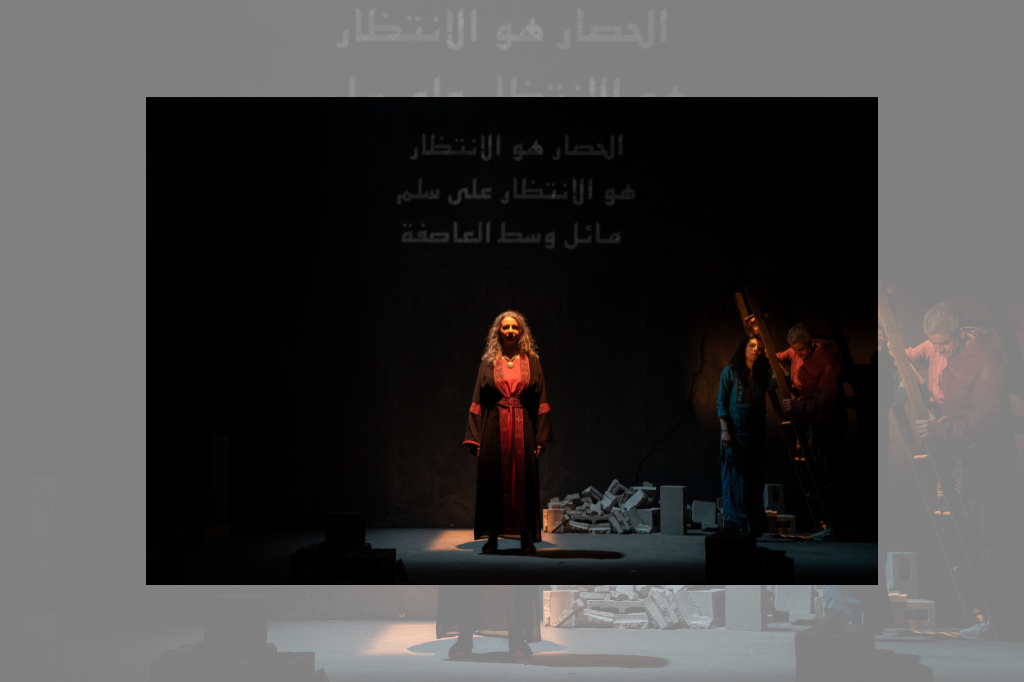

And oh, what poetry it is. Scenographer Trevor Schwellnus has smartly blanketed Theatre Passe Muraille in chalk-written fragments of Tuffaha’s and Darwish’s poems, and as such the words themselves serve as a central character within Rubble — sometimes even more than the humans from whose mouths the poems flow.

A story slowly emerges in the cracks between stanzas: a Palestinian family in Gaza has been warned they have only 58 seconds to save themselves from an incoming blast. But what would you possibly save under such short notice? Wedding albums? College applications? What if you’re an amputee — do you take the time to grab your prosthetic leg, or do you just run?

Suvendrini Lena’s play weaves together poems and plot to occasional success. Slowly, we fall in love with Lena’s characters — Leila, the concerned mother (an affecting Lara Arabian); Mo, the dutiful dad (a heart-wrenching Yousef Kadoura); Majid, the soccer-obsessed son (a charming Sam Khalilieh); Noora, the smart, beautiful daughter (a magnetic Parya Heravi); and The Poet, our narrator and guide through the “rubble” of the family and their words (Roula Said).

It’s a fascinating concept, this story told through fragments of poetry and quick glimpses into everyday family life, but Rubble’s efficacy muddies when The Poet gets involved. Said is easy to watch, a skilled orator, but her narration can interrupt the flow of the story, allowing dense language to persist without context and preventing more cogent moments from developing fully. There are several impactful moments throughout the play which send the heart panging against Schwellnus’ battered, crumbling walls — a fraught exchange between Noora and Leila in particular is beautifully acted and hauntingly staged — but the play’s structure seems to interfere with its storytelling more often than not. Director Beatriz Pizano has assembled a lovely and capable cast, but the play at the heart of the production can’t sustain an 80-minute runtime; there’s just not enough of a chance to connect with the family when the barrage of words gets in the way.

One of Rubble’s more successful choices is Avideh Saadatpajouh’s video and projections, which translate the play into Arabic and suggest colourful, brash graffiti on the walls of the Gaza Strip. Thomas Ryder Payne’s sound design, coupled with Said’s original compositions, also do wonders to suggest the world of the play, interweaving loud explosions with music.

Theatre Passe Muraille’s commitment to audience accessibility in its productions is important, to be sure — the company consistently leads in audience safety initiatives like relaxed performances. But twice now, Theatre Passe Muraille’s projected surtitles have been placed such that they’re inaccessible to roughly half the audience — in Our Place, a show performed entirely in dialect, projections were visible from only one side of the theatre. And again, in Rubble, which includes several sequences in Arabic, surtitles are visible only to audience members seated on the left side of the theatre — and they’re tucked away in a bottom corner, an odd choice given the ample (and frequently used) space for projections on the back wall of Schwellnus’ set. As well, content warnings are posted in the lobby of the theatre, but only under another sheet of paper, meaning you have to go looking for them — given the very loud, very realistic sound effects, those warnings should perhaps be more readily accessible to those who might not think to look for them.

All told, Rubble’s a chance to experience some gorgeous poetry and reflect on the real, all-too-relevant human rights crisis which continues to unfold along the Gaza Strip. Rubble’s story, while at times buried, is as effective as can be when it comes up to the surface — and the weight of the real lives behind it shouldn’t be ignored.

Rubble plays at Theatre Passe Muraille through March 18. Tickets are available here.

Comments