REVIEW: The Flight at Factory Theatre/Theatre Gargantua/b current/Roseneath Theatre/Queen Bess Productions

Elizabeth Coleman, also known as Queen Bess and Brave Bess, is one of those people we should have been taught about. I am happy to have learned her story through the eyes of Beryl Bain in The Flight, now playing in Factory Theatre’s mainspace. Bain is both the playwright and sole performer of the work.

The Flight is a one-woman show presented by Theatre Gargantua, partnered with Queen Bess Productions, b current Performing Arts, and Roseneath Theatre. Usually, a one-person show isn’t my favourite, but this choice made sense within this work. What I love about theatre is the sense of collaboration — though there are many people involved in putting on a production, one-person shows often feel self-centred to me. I sometimes find myself questioning if having a one-person show was a true dramaturgical choice or just one of convenience — I am sure there are many reasons why someone might do a solo show, but that’s just me.

But for The Flight, a solo show made dramaturgical sense to me. See, Bess Coleman was a woman who wanted to make a name for herself. She wanted to prove that aviation was something she could do, and that anyone who wanted to fly, could fly. Elizabeth Coleman wanted to be an inspiration, and with that she didn’t want anyone to mess up her story. The choice to have the work as a one-woman show works, in that Coleman wanted to be in control of how her biography is shown — as a legacy.

Audiences start seated in the theatre, set up as if we’re going to watch a motion picture. A projection on the stage reads in black and white that “popcorn will be served after.” The film starts. We see an image of Coleman in tattered clothes with a walking stick and a backpack. This film is ostensibly Coleman’s biography, but we do not get more than two minutes into the film. Someone in the audience starts heckling that the story is not at all being presented how it should be.

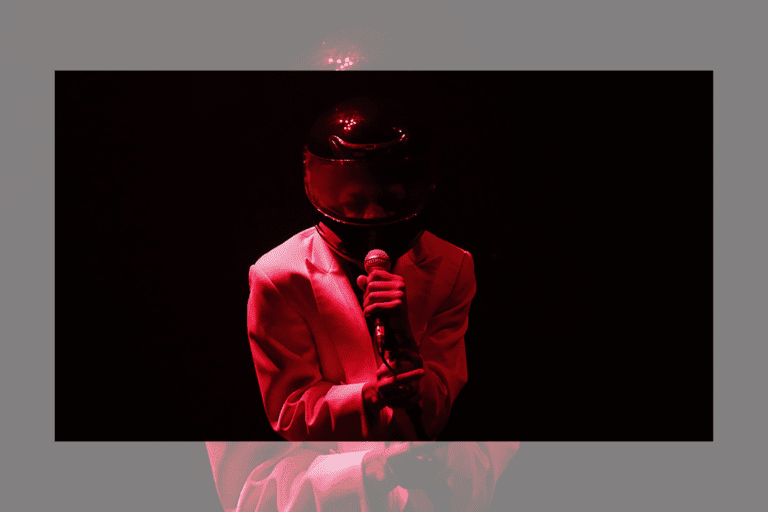

This someone is Bessie Coleman herself, played by Bain. This sequence references a moment that happened in real life, when Bessie was asked to be in a feature-length film named Shadow and Sunshine. The real Elizabeth Coleman walked off the set once she learned the first scene asked for her to be in rags — she refused to be portrayed in that manner. So in, The Flight, we have Coleman literally stop audiences from seeing that depiction of her. She instead steps onto the stage to tell her own story, since no one else seemed to be doing it correctly.

The work uses projections (by Jason J. Brown), and voiceovers/sound (Floydd Ricketts) to propel the story forward. The projections take audiences to the different cities where Coleman traveled — we follow her to Chicago, Paris, and Florida. The projections also help with placing Coleman in her plane, with the aircraft projected behind her as she climbs into it using a step ladder. We also see images of Coleman’s mother, accompanied by her mom’s voice giving Bessie warnings, telling her about her responsibilities taking care of the house. Bessie’s mom, along with the other characters depicted on stage, are all played by Bain.

Marcel Stewart’s direction makes each of the characters distinct. Bain’s character-switching is well timed, and she is able to make Coleman a very loveable person. It felt to me like everyone in the theatre was rooting for her success — we were charmed by Coleman, a brave and sassy young woman taking the stage. This type of storytelling warmed my heart: we do not often see stories of Black people accomplishing things without their trials and tribulations at the forefront. Don’t get me wrong, Coleman had a few things go south for her, but it was her successes that are highlighted in this show. Bessie Coleman grew up in Waxahachie, Texas before moving to Chicago to live with her older brothers at the age of 23. In Chicago she worked as a manicurist, and it was through that job that she heard stories about the war and got interested in flying. Unfortunately, American piloting schools did not accept women nor Black people into their program.

After getting a financial sponsorship from banker Jesse Binga, Coleman had enough money to go to France in order to earn her pilot’s license. Bessie Coleman learned to fly in a Nieuport 564 biplane. And on June 15, 1921, Coleman became the first African American and Native American woman to hold a pilot license.

On April 30th, 1926, Elizabeth Coleman died during a test flight. Ten thousand mourners came to her funeral — she died a hero and an inspiration. Beryl Bain’s writing and performance honours Coleman as she would have wanted to be remembered, in a sweet homage to the activist and trailblazer many may not have previously heard of.

The Flight runs at Factory Theatre from February 10-18. Tickets are available here.

Comments