REVIEW: The Flying Dutchman at Canadian Opera Company

The Canadian Opera Company’s remount production of Richard Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, directed by Christopher Alden (and helmed in this remount by Marilyn Gronsdal), brings to shore multiple levels of intrigue.

A beloved classic that takes place at sea, this opera follows the Flying Dutchman (Johan Reuter) and his eerie ghost crew as he searches to find love to break his cursed fate of being stuck between life and death forever. Luckily (or maybe not so luckily?) Senta (Marjorie Owens) is promised by her father to wed the Dutchman and free him of his nautical curse. (The “ghost ship” theme is perfect timing for the spooky season.)

Under the steady hand of Johannes Debus, Wagner’s lush music is skillfully brought to life by the orchestra — the music is easily recognizable as Wagner through Debus’s skilled direction and attention to dynamics. In addition to its rich polyphonic sound, the piece also effectively uses silence — the orchestra manages to leave an appropriate amount of room for quiet moments to add to the score’s melodramatic feel. The suspense is at its peak in these moments as we wait for the next cue from the orchestra pit, or a subtle movement of one of the performers to move to the next phrase.

What strikes me about the aesthetics of the production is Alden’s (and Gronsdal’s) attention to movement on stage. Bodies move with a precision and clarity that showcases the expressionism of Alden’s directorial conceit, a precision which matches the sharp aesthetics of Allen Moyer’s set design. While the movement in each scene is overly slow at times and occasionally feels a bit forced, it does contribute to a well balanced portrayal of the agony felt by characters like Erik (Christopher Ventris) as well as the angst of the Steersman (Miles Mykkanen).

The singing is unsurprisingly the foundation of this production, the keystone piece that makes this Dutchman’s particular aesthetic work. Specifically, Owens’s empathetic performance as Senta is well executed, and her robust voice provides the character a new sense of maturity. In contrast, Reuter’s Dutchman is appropriately rugged, and his performance of the bass-baritone character booms above the uniform and industrial feel of the chorus who play the gossipy townspeople and ship crew.

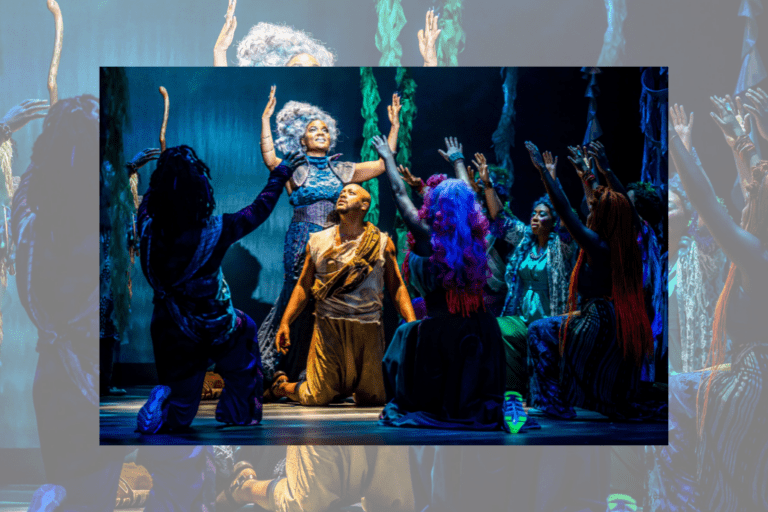

Visually, the production’s experimental aesthetics are consistently interesting and at odds with historical productions of the show. Moyer’s slanted stage gives a feeling of intense exigency, and the sharp corners of the platform and its foundation are ghostly and appropriately unnatural. As characters trek up the slants of the performance space, or gloom about below, not an inch of the playing space is wasted. The unearthly slant is reminiscent of a sinking ship and gives the feeling of urgency in the plot as The Dutchman has only one day to complete his quest for love. Additionally, Anne Militello’s lighting design is more than just dynamic: it is refreshingly vivid due to the ever-changing, and at times even neon lights and colours that pinpoint the narrative’s theme of redemption and love. The lighting is appropriately greenish and dark aboard the Dutchman’s cursed ship, but a hopeful white in the sewing factory as Senta proclaims her obsession with the Dutchman’s portrait.

While the set and the new and current feel of the design of this show complement the music, it’s hard to miss that this cast is predominantly white-presenting, with few visibly BIPOC artists. I can’t help but to think back to Teiya Kasahara 笠原貞野 in their revolutionary performance of The Queen in Me, which cautioned against such lack of representation in an opera industry struggling to foster diversity. Although these productions are only weeks apart I find myself asking again: when will we allow operatic characters to grow beyond what they were centuries ago and accept new bodies in these roles?

Overall, this Flying Dutchman is bound to please both opera vets and newbies alike — even with a story that regularly shows women being submissive to the men around them (and no, it doesn’t pass the Bechdel test). That aside, Debus’s execution of Wagner’s historically experimental compositions, the skilled singers, and Moyer’s visually innovative design will leave audiences thinking about the complexity of each element. While this production surely takes risks in design, I’m still left hoping for a more rigorous approach to diverse casting — the way female-identifying characters are presented onstage and the lack of visibly BIPOC artists in this production feels like a setback that stands in juxtaposition to the production’s fresh aesthetics. In a nearly two-and-a-half-hour long production, surely there is room for better representation and more inclusive casting.

The Flying Dutchman runs at COC through October 23. Tickets are available here.

Comments