REVIEW: The Rage of Narcissus at Expandido Theatre Group/Theatre Passe Muraille

If The Rage of Narcissus was subjected to traditional Canadian dramaturgy, it would likely be an hour long.

Instead, it’s closer to 100 minutes.

The one-man show — a complex, meandering autofiction about Franco-Uruguayan playwright Sergio Blanco (here played by Matthew Romantini) — fluctuates between dryness and brilliance. Unlike many Canadian shows, its tonal and narrative shifts arrive gradually, rather than all at once. This loose structure leaves space for the audience to puzzle over its meaning and luxuriate in its abstraction. Taken as a whole, Latino-led Expandido Theatre Group’s debut production is a beguiling, intellectually engaging prism of an experience that’s unlike much else.

The Rage of Narcissus is a noir turned inside-out and aired to dry. In addition to his playwright duties, the character Sergio is an academic, and he’s giving a talk on the myth of Narcissus at the University of Toronto. (Brazilian director Marcio Beauclair has updated the script with TO references; the funniest name drop is the overpriced Annex cafe L’Espresso Bar Mercurio.) He notices bloodstains on his hotel room floor, and starts to play detective. But his investigation is easy — abnormally so. There’s none of the convoluted plotting of most murder mysteries. He asks about the stains at the front desk, and before he knows it a police investigator is detailing the room’s bloody history.

Romantini’s Sergio recounts these events with unsettling ease. They don’t seem to particularly disturb him; they’re just the facts.

Or are they? Thrice, Romantini steps out of character and speaks to the audience as himself: “I am not Sergio Blanco,” he says. This destabilizes the credibility of everything he says as Sergio. And since he repeatedly reinforces the fact that he’s telling the story “here, right here,” in the Bob Nasmith Innovation Backspace Theatre, these representational questions extend beyond Sergio’s story to concern the act of theatre-making itself.

And also theatre-watching. Throughout, Romantini is sure to include the audience in the proceedings. Everything is done with a wink and to please us. It’s clear Beauclair has directed Romantini to jump at opportunities to disrupt the proceedings and acknowledge the audience: when, at the opening night performance, someone sneezed, he offered a mid-sentence “bless you”; and when someone dropped their phone underneath the seat in front of them, he stopped the show to get it for her. Beyond being funny, these moments challenge the frequent one-sidedness of theatre.

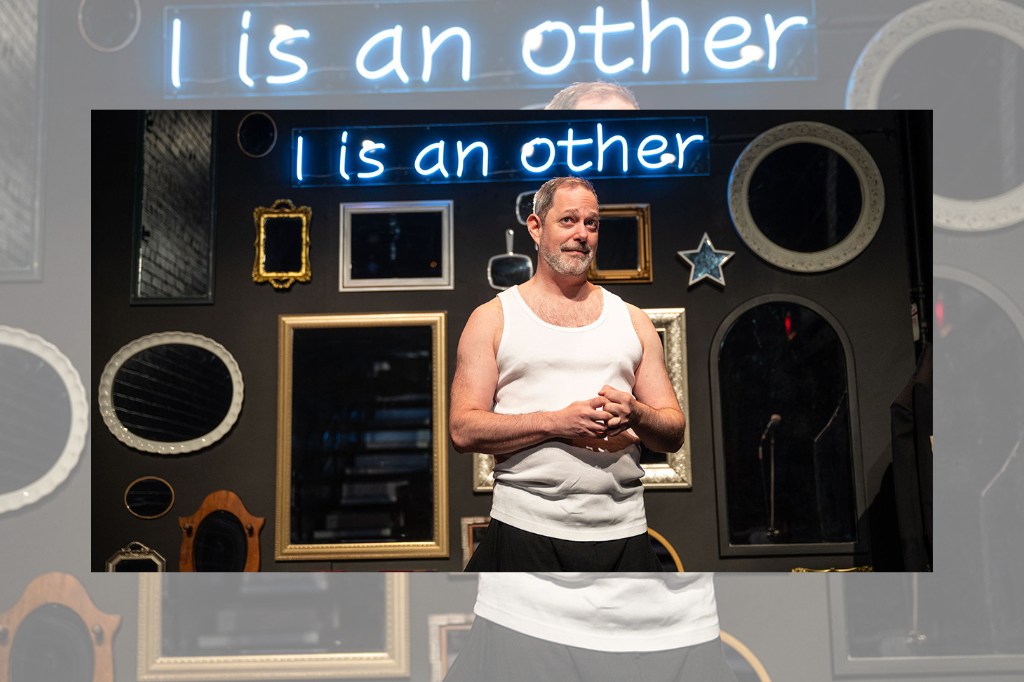

Renato Baldin’s set further implicates the audience in the action. An eclectic array of differently sized mirrors covers the back wall, stretching up towards the ceiling. The audience appears in the mirrors, so they are, at least visually, part of the show. This involvement resonates with Sergio’s lecture in which he compares Narcissus’ gaze to the artist’s gaze. He claims that, like Narcissus, the artist immortalizes themself via their work; and, because audiences contribute to the perpetuation of the artist’s legacy, they too have a stake in this gambit for immortality. Blanco’s presence in the play makes clear that The Rage of Narcissus is not exempt from these charges: it’s as invested in immortality as any other piece of art. And by involving the audience in the play through mirrors, Beauclair underlines their role in the equation.

Lighting designer Brandon Gonçalves further nurtures this metatheatricality. At key moments in the show, the lights go up on the audience and make us self-conscious of our spectatorship. (I’m a front row guy, so I couldn’t feel the lights shift directly, but I could see the effect in the mirrors.) What’s unique about lighting’s role in all this is its ability to shapeshift dramaturgical function: throughout most of the show, Gonçalves’s wonderful design unselfishly supports the action, and plays a big role in giving theatrical texture to the otherwise static monologue. But the lights’ exposure of the audience is a more Brechtian application. The same tool that provided the show’s momentum now ruptures it. The theatrical machine revolts against itself.

An obvious comparison here is Crow’s Theatre’s recent remount of Torquil Campbell’s True Crime, which is also a work of autofiction. They have a few similarities, but the pivotal difference is structure: True Crime is relatively linear, with its relationship to truth hinging on a single key reveal. The Rage of Narcissus’s method is more gradual. Its intoxicating falsehoods seep into your bones slowly, imperceptibly, until you look around and realize the theatre’s walls have been stained with lies the whole time.

This difference reflects larger trends. So often, the workshop process boils Canadian plays down to a single thing they’re saying, and the playwright is encouraged to remould every scene until it contributes to that point. There’s much to love about this dramaturgy; it gives work purpose, keeps boredom at bay. But The Rage of Narcissus is different. It’s unafraid to be boring, unafraid the audience won’t get it. Beauclair and Blanco don’t seem to worry whether theatre is an artform worth skipping Netflix for. They know it is. And that willingness to take up space is both slightly wearing and profoundly beautiful.

The Rage of Narcissus plays at Theatre Passe Muraille until May 28. Tickets are available here

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments