REVIEW: Yerma at Coal Mine Theatre

Content warning: Yerma deals with strong themes including infertility, abortion, miscarriage, domestic abuse, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide. The production also features strobed lighting.

Coal Mine Theatre has made a memorable return to the stage, confidently christening their new home with the Canadian premiere of Simon Stone’s Yerma (after Federico García Lorca), having lost their previous space to a fire last year.

Stone’s high-impact adaptation of the 1934 Spanish classic begins with the christening of another new home as a pair of upwardly-mobile thirtysomethings celebrate the purchase of their first house together. Between swigs of champagne, the nameless main character and her partner John poke fun at themselves and their trendy, gentrified Toronto neighbourhood (originally produced at The Young Vic in the UK, Stone’s Yerma has been made distinctly Torontonian for this production with permission from the playwright).

As they browse expensive furniture online and bicker over the power dynamics of their sex life, it’s clear they are self-aware about the contradictions between who they thought they’d be and who they are becoming. When the topic of having a child comes up, they surprise themselves with how eagerly they take to the idea, finding it almost subversive for a couple like them (progressive, career-focused, and happily unmarried) to do something so very traditional. As they attempt to symbolically crush their birth control pills on the too-plush carpet, they are blissfully unaware of what lies ahead.

Yerma is the directorial debut of Coal Mine’s co-artistic director Diana Bentley, and she’s in good company. Leading the accomplished cast is award-winning film and television star Sarah Gadon, making a stunning theatrical debut as the play’s troubled protagonist. Gadon manages to be both dynamic and respectful in her portrayal of an increasingly self-destructive woman for whom the pain of infertility becomes all-consuming. As the years slip away with each scene, her desperation drives her to jeopardize her journalism career and damage her relationships in pursuit of the child she feels destined to bear. Daren A. Herbert is compelling as her well-meaning but often absent partner, John. The intensity he brings to John’s regret and frustration at watching his partner implode saves the character from becoming just another workaholic husband. Complicating their already tenuous bond is Victor, an ex-lover of Gadon’s character played with charm by Johnathan Sousa, who represents the road not taken and possibly a second chance at motherhood.

Relationships between women in Yerma are no less complicated. Some of the play’s most challenging emotional material takes place between the nameless lead, her sister Mary (Louise Lambert), and her mother, Helen (Martha Burns). Burns is impeccable as the contradictory Helen, gracefully uniting the busybody mom who can’t help asking after grandchildren and the staunch second-wave feminist who is critical of the conventional traps she sees her daughters falling into. Mary, played by Lambert with impressive vulnerability, is in many ways living the mirror image of her sister’s life. Stuck in an abusive marriage, Mary’s fertility prevents her from escaping to a happier situation. As she struggles with postpartum depression, her sister struggles to quell building resentment at how easily Mary is able to conceive.

In Lorca’s original, the title character is called Yerma, meaning barren — a name and a curse Stone’s adaptation replaces, simply calling Gadon’s character “Her.” The name change might speak to the universality of what she’s grappling with, but it also alienates her even further from the other characters. John, Helen, Victor, Mary, even her assistant, Des; all have names of their own. It’s a disquieting decision, and emphasizes how little the other characters (and possibly we, the audience) understand her pain.

Yerma has always wrestled with the way historically taboo subjects like infertility and mental illness are handled publicly, but the definition of “public” is a lot bigger in this adaptation. On top of her day job, Her is a personal blogger and experiences viral success when, egged on with ruthless intensity by Gen Zer Des (Michelle Mohammad), she begins sharing intimate details about her and her family’s lives online. Total honesty or trauma porn? — she walks a fine line and is undeterred by the hurt she causes her family or the consequences that follow. With the stakes impossibly high, it’s hard to empathize with her motivation to continue writing even as her relationships crumble in response. Is it a cathartic exercise for her? Is she creating space for open conversation about infertility? Or is she clinging to the only source of external validation she has left? There’s no satisfying answer to be found in this production, although ultimately Her’s version of catharsis appears to be more violent in nature.

It’s worth pointing out that while the Yerma of Lorca’s original faced intense societal pressure to bear children, the pressure on Her in Stone’s version feels more self-inflicted. If anything, her friends and family are skeptical when she first announces she wants a baby. A high achiever her whole life, she finds herself deeply wanting something that she ultimately isn’t able to control and it destroys her. The tragedy here feels different, and possibly even more uncomfortable, than that of the original text. It’s difficult, messy material; but these are difficult, messy issues.

Adeptly directed by Bentley, Yerma is performed in the round with the audience peering down on the performers from all sides. The scenic design by Kaitlin Hickey (who also designed the lighting) features a sunken, bright white stage that might feel like a ‘60s conversation pit if it wasn’t so sterile.

At first, there’s a disconnect between the more avant-garde aesthetic of the production’s design — both scenic and sonic; tense techno beats cranked all the way up (courtesy of sound designer Keith Thomas) serve as interludes between many scenes of this episodic piece — and the naturalism of the text and performances. As Her’s grasp on reality unravels, so too does the play’s realism. Later scenes are more stylized and heavily symbolic including a pivotal scene late in the play where Her attends a music festival. While the sequence doesn’t share the same clear-eyed vision as the rest of Bentley’s direction throughout the play, any confusion can almost be excused and chalked up to a reflection of Her’s fractured mental state as she wanders through the scene, distraught and intoxicated, as locations and characters warp disjointedly around her.

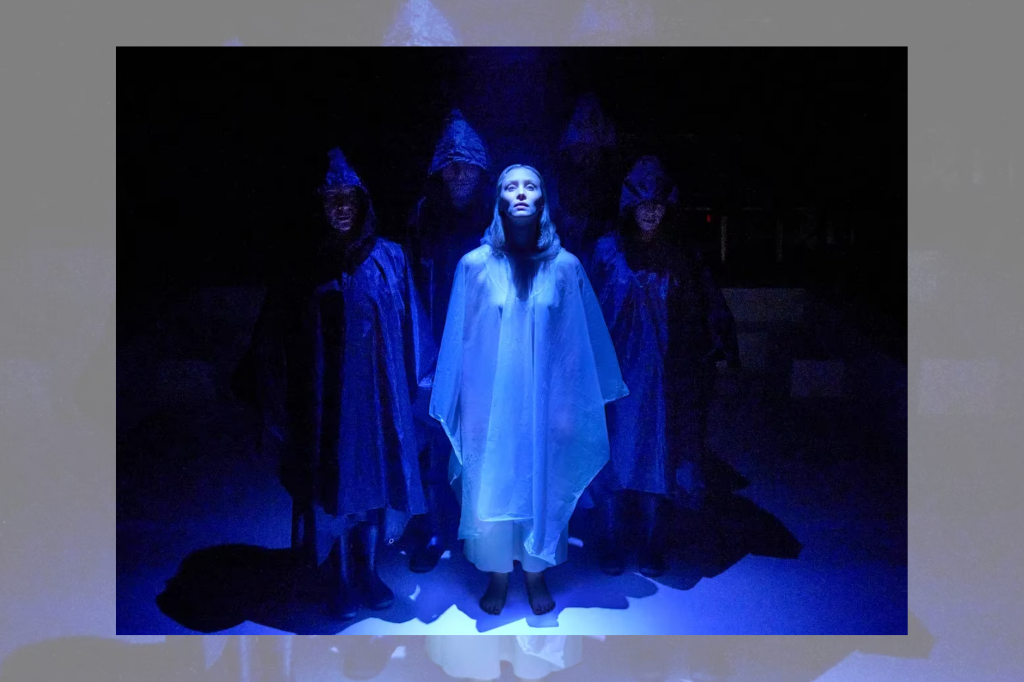

As the story hurtles towards its tragic conclusion, the final moments of the play see Her dressed in a sheer, white shift — somehow still radiantly beautiful as she mourns the child she’s never met. Earlier on, Her rants about the impossible ideal of immaculate conception, but the image of Her presented to us at the end is disturbingly virginal, prompting the question of whether women are ever really able to escape becoming the archetypes expected of them. Maiden, mother, crone: in the most consequential change between Stone’s Yerma and Lorca’s, having failed to become a mother, Her ends her own life, not her husband’s, appearing more maidenlike in that moment than she has the whole play. To me, the image misrepresented the true tragedy of the story – not that Her wasn’t able to conceive (of course, a difficult thing in its own right and not to be belittled) but that her community was ill-equipped to support her in finding meaningful purpose separate from childbearing.

Coal Mine Theatre, Diana Bentley, and the cast of Yerma have delivered a striking production of a difficult play, one I have struggled with across adaptations and invite others to wrestle with as well.

Yerma has been extended February 5 through March 5, 2023 at The Coal Mine Theatre.

Comments