Speaking in Draft: Erum Khan

Speaking in Draft is an interview series in which staff writer Nathaniel Hanula-James speaks with some of the artistic visionaries shaping Canadian theatre today. In a mixture of light-hearted banter and deep dives into artistic practice, this column invites artists to voice nascent manifestoes, ask difficult questions, and throw down the gauntlet at the feet of a glorious, frustrating art form.

There’s a quote by the dancer and choreographer Martha Graham that I hold dear, about the experience of making art: “There is no satisfaction at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”

I was reminded of this quote while transcribing my interview with Erum Khan, a multidisciplinary performer, a theatre and film maker, and the artistic associate at Buddies in Bad Times, the world’s longest-running queer theatre company. Khan’s work is full of a queer divine dissatisfaction with the artistic status quo. At Buddies, she and artistic director ted witzel are redefining the organization’s values for a new era, and wrestling with what it means to be a queer theatre company in Toronto in 2024.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Do you have a favourite spot in Toronto that’s a haven on a rainy day?

My favorite spot in the city right now is the Arch Cafe in Kensington [Market]. I love the people who own it. I love the ambience. It feels like my grandparents’ living room. I go there so often. I’ll read for a bit, and then I’ll leave, and I’m like, “Oh, this is what I want to create.”

So that’s a space, or a vibe, that you strive to create in your own work?

I think so. I’m so craving those spaces where it feels kind of home-y, but it’s outside [the home], and you want to bring people there, and the people you bring will also tell you more about yourself by being there.

Are there theatre spaces where you feel that atmosphere? Or is that something you’d like to create in Toronto?

I do not feel that in theatre spaces. I get so tense, and it feels antithetical to how I think we should be feeling, which is this collective togetherness. Theatre feels so serious, and almost church-like, in a way that’s opposite to what we’re striving for.

What questions are you bringing into your role as artistic associate at Buddies?

[Buddies] is full of so many tensions. It’s full of so much history. I’m trying not to go in naively in a way that’s like, ‘let’s revolutionize this place and radically shift it overnight.’ What is its identity? We have this word, queer. But now all the theatres are doing queer shows. So what exactly are we trying to achieve [at Buddies] that is unique and specific to the place that it is? I think we’ve made queer a passive word when it needs to continuously shift and move and be pulled apart. We’ve made it become synonymous with, like, “the coming-out play.”ted talks about this a lot as well, and working with him is very exciting because I feel like we’re both invested in ideas of: What can queerness be? How are we actually embodying the revolutionary quality of this word, and this politic, and this way of being?

I know we love theatre because it’s live — and yeah, we’re all breathing together, sure — but there’s so much more, you know? I want there to be so much more. We’re alive for such a short amount of time. Let’s be here and do this thing.

I know it’s ever-shifting, but in this moment, what does queer mean to you? Or what does it mean as an active, rather than passive, concept?

The other day, at the 45th anniversary party [for Buddies in Bad Times], I recognized — this is a simple thing — but I am so fucking grateful to be queer. It is such a gift. It is so magical. It feels revolutionary to be in this body, and with these bodies, that are just inherently different or antithetical to what we are supposed to be. So for me, I think that revolutionary aspect is a big one.

To be revolutionary is also to be in resistance, and I think that is also an action. To be a form of resistance is inherently a call to action, and a task that is rooted within liberation. Not that we all have to be breaking down bricks in the system every day. Some of us want to go on the conveyor belt and follow through with the systems that work for us, and we all do in our own ways to survive; but this active force of resistance is what I’m deeply invested in.

The resistance is also in micro-moments. Of course there are the big ones, but it’s also in these small day-to-day interactions. It’s moments of tenderness. Yes, there is a fight, but there is a beauty and a poetic quality to queerness, to this resistance of harsh realities. How are we finding care and love, and actually thinking about these words? Again, it’s active. That’s the queerness I’m embodying or focusing on, I think.

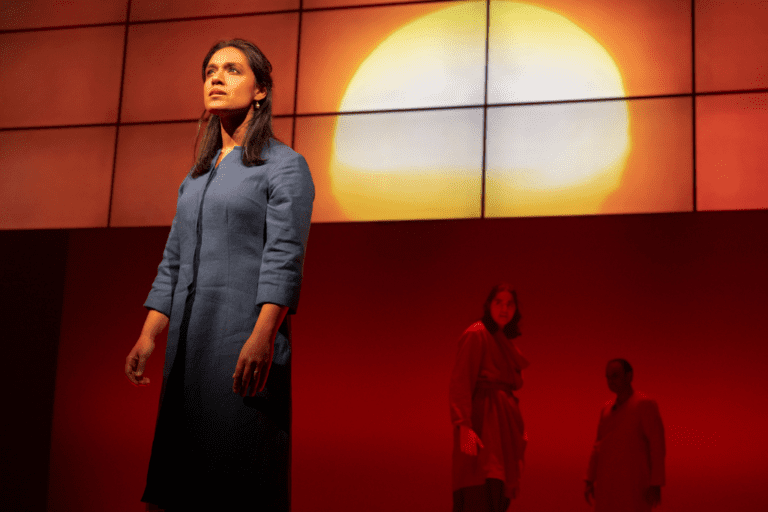

You’re a multidisciplinary artist. I was so struck reading about your piece Noor: in 2018, you invited audiences to observe open rehearsals for the play-in-development, which took place inside a Mongolian yurt located in a courtyard of the Aga Khan museum. I’m also struck by your work as a filmmaker. When you’re moving between theatre and film and other disciplines, is it all the same thing, or does it feel like you’re switching hats?

As you were talking, the first thing that came into my head is that I was raised very much by my grandparents. They are the people I feel like I’m dedicating my life toward. They had three daughters, one of whom is my mother, and the other two are equally my mothers in different ways. They all grew up in a different country almost every year of their lives. We would talk about countries that we don’t discuss in schools here in the same breath as, like, “Oh, we’re going to the grocery store.” We would have these music parties on the weekend and poetry recitations. It was a rich artistic life and childhood that I definitely did not recognize until much later.

That upbringing, in which everything was blended — art, conversation — and that kind of embodiment to me is very artistic. I consider my aunts and my mother very artistic, even though they might not be artists in a professional capitalist way. They’re also, in my opinion, multidisciplinary artists: they move between different forms of being.

As an artist or a creator, I’m really interested in how different forms can engage with worlds differently, but also to the best of their advantage. I’m always asking, “Why is this a play I’m watching? Why isn’t it a novel or a film?” There are reasons why those things can affect us differently, help us to engage with worlds or themes or ideas differently.

When I write, I’ll have an image in mind, and then I’ll think, “Oh, this feels like a film,” whether or not it’s ever going to get made. Then I’ll write it down and I’ll play with it. I’ll know, specifically, that an idea has to be done as a film, because there’s something very specific about the camera and its movement that I really want to play with or explore.

That’s as opposed to the infinite possibilities of live performance, where you can just shift the form halfway and take us wherever you want — which I wish would happen more in theatre. We can truly go anywhere, so let’s go somewhere and be magical.

I loved what you said earlier about liveness. The quality of liveness is often how we justify theatre, but it also feels like the ground floor of the elevator of what theatre can be. For you, what is that thing that differentiates theatre from, say, film or the novel?

Especially in Toronto or Canadian theatre, I think we get stuck in realism. Maybe someone will throw a projection piece in there, but we should be so much further ahead.

We have the capacity for nuance: we leave the theatre, and we’re doing it over snacks at the bar. We also change conversation midway in real life. We’re able to go from something that’s full of depth into something silly in five seconds, then revert back or go completely somewhere else. I think [in developing new work] we think we’re not okay with change; or we think we’re okay with change, but to a certain degree, and we have to make sure everyone catches on so they don’t get the wrong idea of what your intention is. Who cares? Let’s just go somewhere and not know the intention. In an art gallery, you look at a painting and create your own interpretation. Why is that not possible for theatre as well?

I don’t often want to go to the theatre. I’d rather go to a concert, I’d rather go to a dance party. I feel like I’m engaging with so many more exciting ideas and attempts and artists that are also not taking themselves so seriously, so that I actually take them more seriously.

What are some works of art that are giving you life these days? Could be any medium.

Some of them are dance parties. There are parties that are combining a lot of diasporic music, whether it’s North African, Middle Eastern, South Asian. A lot of those parties are starting and I’m like, “Oh my God, this is how we solve world peace,” because we’re all together, and we’re dancing, and we don’t know each other’s music necessarily, but it’s so fun and so active. I don’t have the speaking-answers, but I have my body-answers.

There’s the No Nazar party [in the US]. I like them and the DJs that work with them. I hope they come to Toronto one day.

I guess those are the things that are working for me right now, because also being excited about art — especially in the last few months, especially with a live-streamed genocide — it feels so… so many things, I don’t know. It feels awful. At the same time, we need to gather and be in the collective. Parties like No Nazar are an example of the collective gathering of people who are also aware and in conversation with more beyond just their ego-selves. I mean, the dancing is dancing, but also I see people at these parties wearing keffiyehs, and I’m like, “I feel good here.”

There are also people who are really exciting to me: my trainer, Jazz Kamal, and her body holistic movement practice called Inferno Movement. She’s an incredible artist and human who is embodying her politics and artistic ethos through her everyday practice, which is the kind of person I’m drawn to.

Is there a project of your own, in any medium, that you’re excited about?

I’m trying to write a performance piece around Cleopatra because I’m really interested in her, especially the fact that there is so little written about her, and the majority of it is by men. You start to read about her, and she was so intelligent, and grew up around the world’s largest library, and was raised from age one to be this intelligent leader — but all we know about her is her beauty. How do we dive into so many of these historical women whose image has become one-dimensional?

Also, I’m trying to be a person, because it’s hard. I’m entering my thirties now. It’s exciting. I feel like I lived life in different orders, like a lot of us did. My teenage years felt way more adult than my twenties. Now I’m like, is this the third adolescent wave? Which is exciting.

Is there a tangible step with regard to programming, operations, whatever it may be, that could help create the kind of work and spaces you’re craving in the theatre?

I wish there was more risk, not just in programming, but also in artists, to ask, “How am I actually engaging with ideas in myself and my work that feel rooted in some sort of authenticity, but are also deeply engaging with art [more broadly]?”

It’s important to know what has been made. It doesn’t have to be from here. I love Iranian cinema. So much of my work feels like I’m engaging with those filmmakers’ work. I’m deeply in dialogue with it, or I try to be, and I try to root it into something of myself. I think that’s important, how we’re in conversation with each other, which goes back to the idea of the collective, right? How are we all here together, not just making our own siloed work?

I love collaborating with people in different mediums. I’m like, “Cool. Show me what you know. Let’s respond. Let’s react to it. We talk differently. That’s so great. It’s going to be so frustrating to be in a process with you, probably, but that’s exciting.” That’s active. That’s juicy. It’s not passive.

Thank you so much for this conversation and for your candour!

It was great to respond to your questions.

You can learn more about Buddies in Bad Times here.

Comments