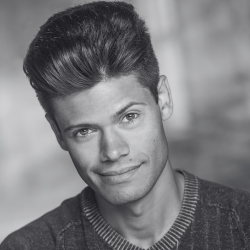

Speaking in Draft: Justin Miller

Speaking in Draft is an interview series in which Intermission staff writer Nathaniel Hanula-James speaks with some of the artistic visionaries shaping Canadian theatre today. In a mixture of lighthearted banter and deep dives into artistic practice, this column invites artists to voice nascent manifestoes, ask difficult questions, and throw down the gauntlets at the feet of a glorious, frustrating artform.

Harbingers of apocalypse are hardly in short supply these days. But I doubt any have looked half as good — or made their audience laugh half so much — as Pearle Harbour. Since moving to Toronto in 2019, I have guffawed, wept, and practiced civil defense drills in the company of Canada’s (self-styled) premiere post-war tragicomedienne. I remember her, roaring into an antique megaphone, in 2020’s production of Agit-Pop! And in 2022’s Distant Early Warning, I watched her remove shards of broken glass from her body after enduring a devastating storm — without missing a beat of her daily razzle-dazzle exercise routine.

Pearle is the ecstatic alter ego of Justin Miller: Actor, bouffon drag clown, performance artist, and teacher extraordinaire. Miller is also Artistic Producer at Tarragon Theatre, where for the past two years he cultivated the Greenhouse Festival, a vital laboratory for non-text based work. Miller celebrated Pearle’s Harbour’s 10th anniversary this past August. We met at Hale Coffee in the Junction earlier this month to chat about his and Pearle’s origin stories, his shapeshifting artistic practice, and why the audience is the main character in everything he does.

How did your love affair with theatre begin?

I’ll give you an insider scoop that nobody’s ever received before. I went to a Catholic elementary school, and we did not have theatre classes, but every year the school made us participate in an oral communications competition. You had to write a speech that was minimum three minutes, maximum five minutes, and present it to your class on any topic you wished. The teachers didn’t help you edit them or anything. Maybe it was just to fill up time.

I fucking killed it. My brother and I were both legends because we would inevitably win. We certainly provided educational content, but we treated it like a stand-up routine. We led with a lot of humour and style. That was my first experience with an audience, and I loved it. Here we are, 22 years later, and I still primarily make my living on direct address and solo shows.

I love this.

The most outrageous speech I think I did was in grade six, when my subject was literally shopping, and the emotional experience of shopping, and being dragged by your mother to the grocery store. I was very discreet as a future homosexual in Catholic school with a topic like that!

I have to credit my mom as well. She helped us whittle and hone those speeches and deliver some really great zingers. Gotta give it up for moms.

When did you start doing drag?

I slipped into drag almost entirely accidentally. When I began dating my now-husband, James, he was into Drag Race, back when it was still an underground phenomenon. I was too much of a pretentious asshole to think that I would enjoy it at all.

Meanwhile, I had just finished studying clown and bouffon with a number of teachers: John Turner from Mump and Smoot, Karen Hines, Philippe Gaulier. The work I wanted to create was dark, satiric clowning. I’d written a solo show in my last year at university. My mentors warmly came and supported — then took me aside and advised me never to perform it again, lest I “kill [my] career before it begins.”

All that was swirling around when one of my dearest friends, Rebecca Ballarin, cast me in her production of Hedwig and the Angry Inch. That was my first time doing drag. When I was in front of the audience as Hedwig for the first time, I discovered that everywhere I wanted to go with an audience, drag catapulted me over their defenses and barriers. It was like this incredible shortcut deep into peoples’ hearts. There was the familiarity and intimacy — literal, emotional, and spiritual – that I had been after in the world of clown.

After that, Rebecca and I began collaborating on a character. Now here we are, ten years later.

Was Pearle’s first appearance at Videofag? [The legendary performance storefront arts space co-founded by William Ellis and Jordan Tannahill, which closed in 2016.]

The first appearance of Pearle Harbour was, rather fortuitously, on August 6, 2014, which was the tenth anniversary of the atomic bomb dropping. It was at — I don’t think it’s there anymore — Unit 102 at Dufferin and Queen. A friend offered me ten minutes in a cabaret night he was putting together. I took 25.

A month and a half later, we booked a night in Videofag and that became our home base for the next two years or so. We were just working, rapid-fire, writing 70-minute long — to call them theatrical productions is generous given the limits of Videofag. Depending on if you had an alley or a proscenium (big scare quotes), you could fit about 18 to 27 seats.

We did three full-length productions, each one six months after the other. To be clear, most of those shows were bad and didn’t work, but that doesn’t matter. When you’re starting anything, you just have to do it because you only discover by doing.

You, like many Speaking in Draft interviewees, are a fashion icon of Toronto Theatre.

That’s very sweet.

There’s a heightened post-war aesthetic that I recognize in Pearle, but also in your own sense of style. Where does that come from?

What I loved in creating Pearle’s character with this post-war aesthetic is the irrepressible, almost idiotic optimism of America at that time: “We can do anything, boys!” There’s something so wonderfully naive and hopeful and childish that I find characterizes a lot of that aesthetic — but there’s also the historical vein of oppression and brutalization of anyone who wasn’t a white cis male: People of colour, queer people, women. I find it rich territory to dig into because of those extreme contradictions; and we are not at all removed from those conflicts.

As I did all those Videofag shows and figured out Pearle more and more, I realized she’s a creature of toxic nostalgia. The lie of nostalgia is that things were better back then, and that we can get back there. In bouffon and clown, it’s irresponsible and just plain mean to attack something in your audience if you don’t own up to it yourself. As a fashion icon of Toronto theatre, I’m obviously too into nostalgia. There are fun parts of that, and there are dark implications to it. Pearle lets me have the cake and eat it too.

In the sense of being able to point out an audience’s yearning for nostalgia and also revel in it?

Yeah, in some way. I’m most interested when things are sincere and ironic in equal magnitude. I like the tactic of over-orthodoxy: Revealing absurdism, not by tearing down the structure, but by embodying the structure to such a passionate degree that it crumbles from its own internal contradictions.

In past conversations, when we’ve talked about Pearle, I’ve noticed that you often refer to her as a separate entity. What’s the relationship between you and Pearle?

I used to be really pedantic. If I was in face and body and costume and hair, and if you referred to me as Justin at all, I was like “Who? What?” It was important to construct her as a character that seemed to live her own life, which is why my social media is her and not me. It’s important that she continues to wreak havoc after the show. I’m less hardline about the division now.

Pearle’s memories of some things are kept in separate filing cabinets in my brain. When I meet somebody that I’ve met as Pearle, as myself, it’s a lot harder to place them. Working in the alternative queer and party scene on Queen West, week after week, interacting with the same people, knowing about their lives, their successes and hardships — some never knew my name, never saw my real eyebrows.

It’s like Pearle is a means to an end, and the end is this deranged bandleader, ringmaster, torchbearer that she becomes for an audience. I’ve been privileged to experience as an audience member, and as a performer, the feeling of sincere community in theatre between strangers. I think there is a deep spiritual void [in our culture] that we have the responsibility to recognize. Why else did the anti-vaccine “Fuck Trudeau” convoy that shut down Ottawa, why did they bring hot tubs and bouncy castles? Ultimately, people need to feel like they are a part of something larger. I think it’s a huge responsibility to bring an audience together. You better have something to offer them, and you better take care of them and leave them better than you found them.

Doesn’t mean you can’t drag them through the muck. One of my heroes, Taylor Mac, says, “I will always keep you safe. It’s not the same thing as comfortable.” I try to live by that edict.

I’m glad you brought up Taylor Mac because I wanted to ask about the role of mentorship in your practice.

My mentor Karen Hines — when I saw her perform Pochsy, her bouffon character, in my first year of university, it was like my head was spinning and steam was pouring out of my ears. I awooga-wooga’d like a Looney Tunes wolf. This is going to sound ridiculously flattering to myself, but I think there’s a special feeling you get every once in a while when you experience an artist’s work, and you recognize them on a deep cellular level as kin. Not that I’m saying I’m as skilled as Karen or Taylor, but they moved me so deeply and in such a profound way that it altered my compass. Then the rest of it fell to me, to journey my way to that new north.

I was one of about 500 people who were at the only performance of Taylor Mac’s A 24-Decade History of Popular Music, which was a 24-hour-long durational performance from 12 p.m. Saturday to 12 p.m. Sunday in Brooklyn in 2016. That was one of the best days of my entire life: Seeing Taylor be with an audience in such an utterly vulnerable way, with such strength in that vulnerability, making it about us in the room together and the community that we were building. That’s when my work as Pearle started getting good: When I didn’t focus on her or me as much, to try to convince you how clever I was, but when I started listening for real to the audience.

One of the things I learned from being able to talk to Taylor human-to-human was that this thing we do, this drag performance art, a lot of times people don’t know where to put it. I’ve really benefited from catching the wave of popularity from RuPaul’s Drag Race. I’ve also benefited from the fact that my clown ended up being a female character and not my own gender, because I think that angle has gotten me a lot of gigs and grants that I might not have had access to otherwise. But I also know that it’s kept me out of institutions.

Taylor spoke of making yourself the institution. So Pearle runs a revival tent in Chautauqua, and then has a doomsday cabaret in Agit-Pop, and then a post-apocalyptic romance in Distant Early Warning; but through all those shifting genres, she’s the institution.

If you could wave a magic wand and change one thing about Toronto theatre, what would it be?

More entertainment, please! I love to laugh. Some of the most impactful and meaningful experiences I’ve had have been shared through a comedic lens. I think you have a far better chance of actually changing people with comedy, because it’s in moments of surprise and subversion of expectation that you have a chance to knock them off their balance, and maybe show them something new.

What’s next for Pearle?

Her next thing is going to be on screen. I’m in the midst of post-production right now for a short we shot in March of this year, which is going to be very demented and very fun. I made it with some really wonderful friends, like Wayne Burns, Alaine Hutton of Lester Trips Theatre, and Sonja Rainey.

You’re now a mentor in your own right, as a teacher of clown and as the drag consultant on the Stratford Festival’s 2024 production of La Cage Aux Folles. What’s a core value you try to impart?

The work starts with impulse and imagination, and exploring all the beautiful facets and colours that we have. We’re all gifted with the same capacity for both the angelic and the monstrous. It’s okay to find both those impulses inside yourself.

I try to give permission within the playground of theatre or clown or drag to indulge your imagination in the most extreme ways that you can and that you want. Then, when you’re at the point when you’re sharing with an audience, I’m a little less gentle: I ask you to truly listen, because what’s happening in the audience is always infinitely grander that whatever’s onstage.

Kurt Vonnegut once said that “practicing an art form is a way to grow your soul.” I think that’s really true of my experience. As a fallen Catholic, clown is the closest thing I have to a spiritual practice.

One last question: What is your current pop culture obsession?

Probably Niles from Frasier.

Wait, like the reboot?

No, not the reboot. Niles isn’t part of the reboot. We only just started watching Frasier, my husband and I. It’s fitting that when you say “current pop culture obsession,” I reach for something that’s 25 years old. True nostalgia queen that I am!

It’s so good!

David Hyde Pierce, as Niles, is the most extraordinary clown. The physical performance and precision is so skillful, but it’s all done in a very minor key and very small, except for a couple key moments throughout the series.

I’m kind of staggered by it because, when I was a kid growing up in the 90s, I remember seeing a lot about Seinfeld and Kramer, who is another iconic clown. If Kramer is like a Charlie Chaplin, though — more outward energy — Niles is like a Buster Keaton: Inward, subtle, small. I don’t think David Hyde Pierce has been given the appropriate pop culture placement, value, and currency for the genius of that clown.

Give David Hyde Pierce his flowers.

It’s pretty fantastic he turned them down for the reboot.

Hopefully this article leads to a Frasier renaissance.

Absolutely.

Comments