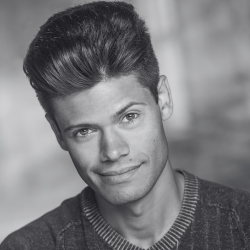

Speaking in Draft: Rachel Forbes

Speaking in Draft is an interview series in which staff writer Nathaniel Hanula-James speaks with some of the artistic visionaries shaping Canadian theatre today. In a mixture of light-hearted banter and deep dives into artistic practice, this column invites artists to voice nascent manifestoes, ask difficult questions, and throw down the gauntlet at the feet of a glorious, frustrating artform.

Rachel Forbes’ wide-ranging career has set this artist in a league of her own. The award-winning set and costume designer’s work has appeared across the country in productions by the Shaw Festival, Buddies in Bad Times, Obsidian Theatre, Neptune Theatre, Centaur Theatre, and more. Forbes won a Dora Mavor Moore Award for costume design in 2019, for The Brothers Size at Soulpepper, and a Merritt Award that same year for her set design of The Bridge, a 2b and Neptune co-production. When I reached out to Forbes about having a conversion, I was delighted to learn that she’d be Zooming in from Prague, where she’s embarked on the next step of her journey as a designer.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

So the first thing I want to ask: why Prague?

I’m doing a master’s degree at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. I started teaching a little bit in the last few years. I thought, ‘I can’t carry on my design career the way I have forever.’ The way I work is too intense. (Laughs.) It sort of drives your body into the ground. Apparently, that’s the only way I know how to exist. You’ve got to get a master’s if you want to teach more formally; and I wanted to see if there was something interesting about a European market. It’s a nice thing for me right now, to be somewhere different and see how they do stuff.

What was your path into theatre, and how did you come to set and costume design?

I started doing drama in high school — you know how it is — and found that what really drew me in was collaboration. I found a bunch of other weird people. I think this happens to a lot of teenagers: You find other strange folks and decide to stick around with them. I was writing and directing and doing everything. Not acting! I hated acting. I didn’t want people to look at me while I spoke. (Laughs.) Still true to this day. As for design, I really like doing things with my hands. I really like to make things, think about making things, think about space.

How do you approach space as a designer?

I feel that I’m highly sensitive to space. When I walk into a room, I can feel the energy of that room, if that makes sense: how it flows in and out through doors, how things are arranged. All of these things really affect me. Manipulating that to help tell a story is what I find exciting.

When you’re beginning a new project, what’s your way in?

My first way in is always through the story. That might sound obvious, but I mean it in the sense that I don’t like to come to a first design meeting with an idea. I don’t want to have something that I already think; I want to have a shared understanding of what the story we’re telling is, before I even start to think about what the visual world might be.

One of the first things that comes to my mind is colour. Sometimes I’ll do colour palettes for myself; sometimes it starts from some abstract image I’ve gotten from the play. I’ll read [the script], I’ll think of something quite random, then I’ll start researching and see what rabbit hole I end up in, and then I’ll take that back for conversation with somebody else. It usually takes me quite a while to get to an actual idea of what the set will be. Usually I want to think in circles, near the actual idea, before I get there.

The other thing that really matters: I think that all set design is site-specific. Each theatre is its own specific space. I’m always working with that. If it’s a proscenium house, I don’t think of it as just an opening: It’s an opening inside of a space, inside of another space. The way that the audience is going to experience that room is going to be different than in some other proscenium theatre.

Is your process around set design also your process for costume design?

I have to confess something: I became a costume designer completely by accident. I always loved to sew, since I was a teenager, but I never thought I would do costume design until after I graduated university.

So often, my brain goes through set first. That’s not always true — but even if I’m just doing the costume design, especially because set usually happens first, it’s nice for me to understand what kind of world we’re creating together as a whole team. One of my biggest frustrations is when the set and costumes look like they’re in different universes. It drives me crazy — unless that’s intentional, but even then you can usually tell that there’s a link.

My costume design process is different from set design, though not entirely. Often, one of the first things I think about is still colour; but from there, it’s about analyzing characters and power structures, and the way people relate to each other. What people are trying to say to each other, or even to themselves, with their clothing is usually how I make my way into costume.

Sometimes you have to create a world that’s not the world we live in, in which case again the process is different. One of the last shows I did before I came to Prague was Of the Sea, an opera [composed by Ian Cusson with a libretto by Kanika Ambrose, and co-produced by Tapestry Opera and Obsidian Theatre.] Of the Sea took place at the bottom of the ocean. The characters were all people who, over the course of hundreds of years, had fallen or jumped from slave ships in the Middle Passage. In the world of the play, all these folks were existing in a kind of limbo in a society outside of our world, and also with only Black people. I felt like I was starting worlds from the ground up. You still have to think about power structures and all these other things, but first you have to come up with what the world even is.

Have there been one or two projects in the amazing career you’ve had, and continue to have, that stand out as a unique joy or a unique challenge to work on?

Of the Sea is a good example, because of creating a world from scratch. On that one, a hair and makeup designer and I collaborated, which is something I’ve never really had before, because there needed to be this element of weird: The wigs were colourful and big and strange and fun. Philip Aikin, who directed, was just like, ‘Go ahead. Do your thing.’ Of the Sea was such a busy process and so fast; I just ran with it and went on a whole journey. It was so free.

I think back to Black Boys [which Saga Collectif premiered in Toronto in 2016] a lot because it was one of my favourite things to work on. I don’t think I’ve ever had that much time on something. I think there must have been two workshops and I was with the project for a while before it came to production. The process was super collaborative, because at times [performers and co-creators Stephen Jackman-Torkoff, Tawiah M’Carthy, and Thomas Antony Olajide] were playing versions of themselves. A lot of what I did was, like, wrangle Stephen’s wardrobe. They just kept bringing things in and I was like, ‘Okay, let’s see how to make this work.’ So this kind of collaborativeness with the performers, not just with the director, was very interesting.

I’ve worked on a couple shows with d’bi.young anitafrika. We also had this relationship where — because there’s not always a script — they would tell me what the piece was about, and then they would give me some images, some things to think about, and I would go from there. Often, I wouldn’t even show them beforehand what I was going to do. I didn’t even really know what I was going to do! I’d go in and just — for Esu Crossing the Middle Passage, I just went in and started painting the floor. It was in the Storefront Theatre way back in the day, on Bloor near Ossington. The design combined the shape of the belly of a ship, a crossroads for Esu, and abstracted Adinkra symbols. I had a rough idea, and then I just did it. d’bi was like, ‘I love it!,’ and I was like, ‘It’s a good thing you love it, cause it’s there now.’

How would you define your voice as a designer?

One of the things I know about myself is that I’m not a huge fan of creating naturalism. I like to watch a play that lives in it, and when someone’s done it really well, I’m like, ‘Mmm, that’s great.’ But I’ve always been a person who, onstage, doesn’t want to create a space that’s real. Because why? I might as well go make films, in that case, and make a lot more money. I like [sets] that are a playground for the work. Sometimes I prefer to just create a space that has enough versatility inside of it that we can change it actively, and I don’t have to decide everything before rehearsal starts.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to answer that question [about my voice]. I don’t think that point has come yet, now that I think about it for real. I think I know better what tools I like. That’s all I’ve really found.

As an actor, I’ve experienced how much a costume can shape the choices I make onstage and reveal new things about a character. Does costuming ever feel like a collaboration between yourself and an actor?

The level of collaboration depends on what you’re doing. There are so many times when you have to fully design a costume and commit to it before the performer arrives. Sometimes you can only do so much; and sometimes it’s like, ‘I’m going back to the mall, what do we really need to do here?’ I’ve had times where we figure it out together, or where the initial sketch meant basically nothing in the end because everything changed.

I’ve also had times where, especially when I’m working with an actor I’ve never worked with before, sometimes when I meet the person I think ‘Oh, I did this or that wrong in the costume because I didn’t know you were you. I need to come at this again in a slightly different way.’ Now I’m lucky in that I work with a lot of people again and again, and I have a sense of them in some way, who they are as people.

With The Doctor’s Dilemma at the Shaw Festival in 2022, director Diana Donnellyhad updated the script to be set in the present day. We arranged with the festival to have a paid session with the performers in between my preliminary designs and my final designs. I came with everything and said, ‘This is what I think of your character. What do you think?’ By the time we got to the first day, the actors already knew what was coming and they had helped to guide it. I’ve never quite worked exactly like this again, where we were able to have a real meeting before I finalized the designs, which is usually at least a month ahead of rehearsals. That collaborative spirit carried itself all the way through: Even performers I’d worked with before had a way of talking to me that was different, because we’d already talked about costuming months ago.

Now that you’ve started teaching and are also on the board of the Associated Designers of Canada, how are you thinking about your role as a mentor?

Mentorship is really important to me because it’s how I came to be. I actually never did a set or costume design at school. Then I worked with Astrid Janson for two years, and that’s where I got my design education. You can’t learn all the stuff you need to learn in school. A lot of it you learn on the job. Maybe I made a few less mistakes, or there were certain things I was ready for, because I’d been mentored.

Mentorship is also important to me because — and this is me very much speaking in draft — of all the [creative roles] that are diversifying, specifically racially, the ones that happen off the stage are diversifying much more slowly than the ones that happen on the stage. I feel I have a specific place inside of the industry, and so it’s important to me, if I can, to try to help people into it.

It depends so much on the artists themselves, what advice I might have for them. One thing I like to tell people is that it’s hard. It’s really, really hard. As a designer, you have to take on multiple projects, or projects are going to overlap in ways that are sometimes really icky. Everybody is going to learn their points of burnout differently. I can’t think of a single designer, or a single theatre practitioner, who doesn’t know about this threat of burnout.

Sometimes I’m like, let me just teach you something practical: budgets, or how to achieve a certain trick with fabric. I also think about how, especially when [an emerging designer goes] from indie to established, there’s this point where they might think, ‘When I was doing this myself, I could do some crazy stuff; but now that I’m at a big company, they say it costs too much.’ I’m like, ‘Yes, that’s because they’re paying someone for real to do all those things, and they should.’ They have to start getting used to the fact that things cost money, and time equals money in a budget. Someone’s going to do [this part of a project], and they’re actually going to do it better than you did it for yourself. When you’re at the Shaw Festival, they’re not going to give you the five-minute carve, because they take pride in their work.

It’s hard to meet the directors you want to work with. Sometimes relationships, when you’re working, are toxic; and sometimes they’re amazing; and it takes a long time to find the qualities that make them amazing. Whatever I can help people with, I’m happy to.

Thank you so much for this conversation.

Thanks for asking me. This was pretty fun, actually. Not that I don’t get to talk about myself enough! (Laughs.) Now that I’m doing a master’s it’s a very inward-looking time. But yeah, this was great.

Comments