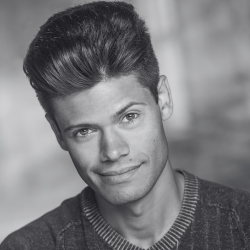

Speaking in Draft: Theresa Cutknife

Speaking in Draft is an interview series in which Intermission staff writer Nathaniel Hanula-James speaks with some of the artistic visionaries shaping Canadian theatre today. In a mixture of light-hearted banter and deep dives into artistic practice, this column invites artists to voice nascent manifestoes, ask difficult questions, and throw down the gauntlets at the feet of a glorious, frustrating artform.

The first time I saw Theresa Cutknife perform was in 2022, in Aluna Theatre and Modern Times Stage Company’s production of Federico Garcia Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba, directed by Soheil Parsa. Bernarda Alba was one of Cutknife’s first professional shows out of theatre school: she hails from Maskwacîs, Alberta, on Treaty 6 Territory (she is a member of the Samson Cree Nation), and moved to Toronto in 2016 to attend the Centre for Indigenous Theatre.

In The House of Bernarda Alba, Cutknife gave a standout, fully embodied performance as one of the daughters of the production’s titular matriarch. Since then, my admiration for this multidisciplinary Nehiyaw/Puerto Rican artist has only grown. Her practice encompasses performing, playwriting, producing, and directing. It was my pleasure to speak with Cutknife about her creative process, her upcoming projects, and her vital perspectives on our industry.

In this humid Toronto weather, where do you go in the city to beat the heat?

When I can, I like to go down to the water. I used to live in the East End, and going down to the beach was so easy, but now it’s more of an adventure. In an ideal situation, I could just walk out and boom! The water would be right there.

What was the first moment where you realized theatre was what you wanted to do?

When I was younger — even younger than high school — I had this silly thought in my brain that my bedroom was soundproof, and I’d be singing to myself all the time. Eventually my parents were like, ‘Hey, would you want to take singing lessons?’ And I was like ‘Why do you ask?’

Once I found out that my bedroom was not in fact soundproof, I started singing to myself directly after school before my parents got home. I’d be singing to myself, and I was like, ‘Am I tone deaf? I don’t know.’ So I auditioned for the school musical — which was Seussical — purely to find out if I was tone deaf. I found out I wasn’t tone deaf, and I got a part.

From there I took more drama classes and started doing community musical theatre. I threw myself in, because it was the first time I felt like ‘Hey, this is something I wanna do. This could be my thing.’

Once I left high school and started going to the University of Lethbridge, I thought I was going to be a drama teacher; but in my first year I realized I didn’t want to be a teacher, so I transferred to the University of Alberta. I was doing a Bachelor of Arts in Drama with a minor in Native Studies for four years. By the end of it I was like, ‘I gotta get out of here.’

Then I happened to find the Centre for Indigenous Theatre. I think it was through a random Google search. The program was similar to what I was doing, but with more of the practical stuff I wanted to learn. I was lucky: I had a supportive family who said that if this was something I wanted to do, I should go for it. I decided I was going to move to Toronto, go to this school, and try to be an actor.

What was your experience like at the Centre for Indigenous Theatre?

Even though students had varying degrees of experience with theatre and drama, we all had this foundation of being Indigenous. We all, in one way or another, had these shared values. It was also a smaller school, with smaller classes, so we had more specialized time with instructors. I hear peoples’ — for lack of a better phrase — horror stories from the various different [drama] programs in Toronto and all over the country. I would say CIT is not without its flaws, but the specific kind of scars and trauma that people at other institutions were left with — I never had that specific experience. I feel very lucky to have gone through that program.

How would you articulate your process as a performer?

I like to spend a lot of time with the script. I try to read it, then put it down for a bit, then come back and read it again. I usually like to read it all out loud to myself, just to get the feel of the words. That also helps with memorization, and following the trajectory of the story, prior to getting into the room.

Once we get into tacking down blocking, the transfer of the words — from being on the page to becoming in my body — is what really helps me. I enjoy when processes do explorations of character in different ways, like in school when you explore leading with your knees, or your ear, or think of an animal for this character. [Laughing] Maybe some people are like ‘Ugh’ about that. But I love it because it takes me out of my head and being so cerebral. There’s just something in the body that really grounds me, personally, as an actor.

I love what you said about words becoming embodied. What does that feel like to you in the moment?

There isn’t that anxiety of trying to think of where you are, or what’s next. That transfer — it’s hard to explain — but it feels like there’s a natural flow to the words, especially when you know what you’re saying and why you’re saying it. It’s almost like choreography, in a way. Not in the sense of ‘I move here on this line,’ though that’s there to anchor you. It’s more that I’m following this thought pattern, this thought train, and it brings me into this next space or next tactic or motive.

Are there any projects you’re working on currently that you’d like to talk about?

This summer I’ll be going home to Edmonton to do research for a play that I got a recommender grant for from Native Earth, about the rematriation and repatriation of sacred items in museums.

The perspective that I’m trying to explore is what happens after the returning of those items. I don’t want to write a story that’s like, ‘Please give us our stuff back.’ I don’t want to beg for it. I want to explore what it would mean for a community to have those things returned, to have those ancestors back in their homelands, and the different perspectives there might be on that. I’ve been describing it as ‘Night at the Museum-esque’ but more Indigenous.

I’m also working with [artist and artsworker] Emily Jung on a project for SummerWorks, in collaboration with Baram Company, a South Korean theatre company centred around eco-dramaturgy. I’m sure you’re going to follow up with, ‘What is eco-dramaturgy?’

I am!

I’m no expert, but from what I understand, eco-dramaturgy is more about de-centring a human perspective and bringing forward a non-human perspective, and also trying to think about the relationship between human and non-human entities.

Earlier you mentioned that you’re grateful to have had a pretty healthy theatre school experience. In your professional life thus far, is there a process that you’ve been part of that’s felt particularly grounded in good ways of working?

A stand-out for me would be My Sister’s Rage, [a production written and directed by Yolanda Bonnell which premiered in 2022, and was produced by Tarragon Theatre with Studio 180 and TO Live.]

Working with Yolanda is such an incredible experience. Even before rehearsal started, Yolanda was very adamant and particular about asking what wellness and health meant for folks, what were the things that people needed for them to have a good experience. There was even a Google form asking, ‘What are things you want or need in the room?’

When we got into rehearsal there was this beautiful wellness table. We had snacks; we had medicines; there were stuffed animals; we had yoga mats, and blankets and all these things that people had said it would be nice to have. I don’t think I’ve ever seen that before, or since, but for a creator, a director, a leader to have such care at the forefront of their brain was so beautiful. It’s something that’s informed me and how I want to work.

We had shorter rehearsal days through Yolanda’s hard work of negotiations with the theatre. We weren’t doing the six-day rehearsal period until we had to. For the majority of the time it was Monday to Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. I was coming off of working on a TV show as an assistant, so those were 16-hour days. To go from that to six-hour days — it was beautiful!

We didn’t have any two-show days. That was something that Yolanda had also negotiated. Two-show days are brutal for actors; it’s surprising that we’re still doing that. To know that there’s a tangible example of someone like Yolanda sticking to their principles is something I keep in mind. Just because we’ve been working in one way forever doesn’t mean it needs to stay that way.

If you could wave a magic wand and change one thing about so-called Canadian theatre, what would it be?

I still feel like we make things too hard for ourselves or for each other. I’m not naive about the fact that there are so many things that are outside our scope of control. Systemically, the arts are chronically underfunded, and we’re at the mercy of whatever government is voted in. I understand how that affects granting systems, and how that trickles down into the various companies, and how we’re all trying to claw at the very same pieces of the pie. At the same time, with all the seemingly immovable systemic barriers, why are we putting barriers on each other, on ourselves? I think sometimes the community mindset in theatre can be more theoretical as opposed to practical.

It feels like the track you’re supposed to go on is you go to theatre school, then maybe you apply for a playwright unit, or a festival, or a residency. You develop a certain thing to a certain point. You showcase it. Nothing happens. You therefore apply to a different residency, a different program. Maybe you develop that thing a little bit more, a different project. You showcase it again. It dies in the water; or maybe you do get to develop it, but it’s over such a long period of time that even if a theatre does pick it up, overall the support you’ve had is so minimal.

These tracks only benefit people who have the privilege to continually be supported, in ways that don’t take them out of the scene. Of course, we all have to make money and make different sacrifices just to pay the bills, because this city is so horribly overpriced. But why? Why do we have to suffer to feel like we’ve paid our dues to the industry?

What I’m hearing is dissatisfaction with the relentless pace of trying to stay in the game: a game that’s only realistic for some people who might have certain resources. I’m also hearing a wish for more ease and spontaneity in how theatre can be produced, without endless development processes.

To distill it down even further, if I could wave a magic wand, I would make it so that folks don’t have to suffer for their art. Some people might disagree with that, and say that art is suffering.

Of course you have to do the work — but I’m talking about not having to prove that you’re serious about your work because you paid your dues for it.

Maybe another thing would be that spirit of experimentation. It feels like, again, because of the lack of resources, you’ve got to get it right the first time. Maybe we need to take away the pressure of it all.

I want to quickly shout out Labour in the Arts. They do these Zone Out and Craft & Chill events where you literally cannot talk about work. The last one I went to was last summer, at the Music Gardens down by the water. There were snacks. There was crafting. I feel like a way to combat that [endless] performance arts workers have to do is creating events and spaces where we just tell people, ‘You can’t talk about work. We don’t care. We don’t want to hear about the thing you’re working on. Just sit, meet someone or make a little craft.’ They’re creating more spaces for people to just be.

I agree with all of this wholeheartedly! On a lighter note, what are you looking forward to in the rest of the summer?

I’m looking forward to Alberta sunsets. I know that the sun is beautiful anywhere, but the sky is bigger out there. I also haven’t been back home in a long time, so I’m excited to go to my community’s Pow Wow, and to see my family and spend time with them, and to be part of whatever adventures happen. I love those days when people are like, ‘Should we go to the beach today?’ Those last-minute, out of the blue events. I live for those types of things.

Thank you so much for this conversation.

I hope you have a good rest of your week, and thanks so much.

Comments