Spotlight: Seana McKenna

Seana McKenna has played some less-than-perfect mothers in her illustrious career. They’ve ranged from morphine-addicted Mary Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night all the way down to the eponymous sorceress of Euripides’s Medea, who wreaks revenge against her faithless husband by killing their sons.

By those standards, Fran Price, her role in Andrew Bovell’s Things I Know to be True, isn’t such a bad mom. Sure, she can be hard on her four adult children, and she doesn’t show a lot of sympathy for their problems.

But then again, she hasn’t had it easy herself — like many women, she’s spent her life balancing a full-time occupation with running a household.

“My job is to try and understand Fran,” said McKenna, unpacking the character during an interview between rehearsals for Bovell’s play. The Australian playwright’s powerful 2016 family drama, receiving its Canadian premiere this February from Toronto’s Company Theatre and Mirvish Productions, follows a tumultuous year in the life of the Prices, a working-class couple, as they confront various crises in the lives of their grown-up kids. McKenna agrees that Fran, a registered nurse with a no-nonsense approach, can initially seem like “the bad guy” in the play.

“She’s blunt, she can be abrasive, she’s always on the go,” she said. It’s much easier to like Bob, Fran’s laidback husband, a retired auto worker and avid gardener, played by Tom McCamus.

“Everyone loves Tom, everyone loves the dad, but she’s the mediator,” McKenna said. “She’s trying to keep the family going, it’s the most important thing to her. At the same time, she works because she thinks she’d go crazy if she didn’t.”

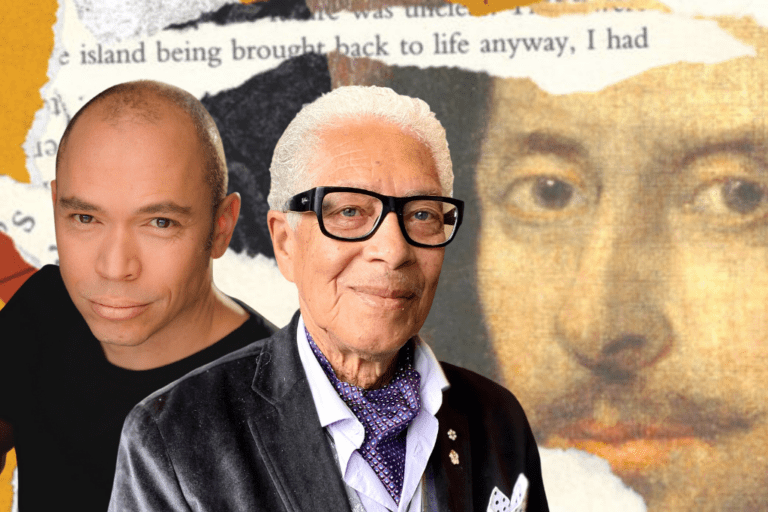

As she empathizes with Fran, you get a taste of the sharp intelligence and shrewd insight into character that McKenna is famous for. The recipient of an Order of Canada and winner of a clutch of theatre awards — not to mention a mountain of critical bouquets — during her four decades onstage, she’s routinely referred to as one of the country’s finest actors.

But she refuses to coast on her reputation.

“She’s extremely inquisitive, with a mind that is continually turning things over,” observed McKenna’s real-life husband, director Miles Potter, speaking by phone from the couple’s Stratford home. She applies the same Socratic method to a contemporary script like Bovell’s as she does to the classics. The results are often thrillingly bold but always carefully considered portrayals, in which she allows the audience to see through the eyes of even the most egregious figures, like Medea or that twisted embodiment of evil ambition, Richard III.

“She was absolutely riveting as Richard,” enthused Antoni Cimolino, artistic director of the Stratford Festival, where McKenna gave a compellingly androgynous interpretation of the wily usurper in 2011. “She was totally reptilian and yet magnetic.”

She was totally reptilian and yet magnetic.

McKenna says her inquiring approach hasn’t always been welcome by directors. “I’m often told I have too many questions,” she told me. “But how will I learn if I don’t ask?”

Cimolino admitted he was put off by it the first time he directed her, in the festival’s 1998 staging of Tennessee Williams’s The Night of the Iguana, until he realized her questions weren’t objections to his directing choices. “They were part of an honest effort to understand more deeply,” he said.

When creating a role, McKenna also brings everything to the table in terms of personal experience. “I don’t know that there’s a barrier,” she said. “Of course, you play Medea, someone who murders her children, you have to use your imaginative forces, but it’s a question of degrees. Have you ever felt betrayed? Have you ever felt you were losing something you didn’t want to lose? And if you haven’t, there were moments that got close. So, you just say, ‘Okay, what’s that like, 10,000 times?’”

McKenna, unlike Fran, has only one adult child — her son, television and film actor Callan Potter — but she knows what it’s like to be a working mother. She also knows all about long marriages. She and Potter have been together since 1980.

In fact, on a professional level, theirs has been one of the most successful husband-and-wife teams in Canadian theatre. Potter has been at the helm of many of McKenna’s stage triumphs, both at Stratford and at Canada’s major regional theatres, notably Winnipeg’s Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre. Their many shows together have included the aforementioned Richard III and Medea, and a series of Tennessee Williams classics – most memorably, their 2005 Stratford rediscovery of Orpheus Descending, with McKenna as a smouldering Lady Torrance, which was remounted in Winnipeg and Toronto and won McKenna her third Dora Mavor Moore Award.

On a personal level, McKenna and Potter hit it off almost from Day One. They met when she was fresh from theatre school and Potter, who was directing a play at the fledgling Blyth Festival, needed a late replacement for an actor who had dropped out.

“She was introduced to me as someone who was very good at learning lines,” Potter recalled. “I said, ‘Great, we’ll check her out!’”

The offstage romance quickly followed.

“I’d like to say we waited to get together until the opening of our first show together, but we didn’t,” McKenna said, laughing. “It happened pretty fast. He was something. There was always ease of communication. And there was also great respect as artists in the theatre.”

Truth be told, McKenna says her first encounter with Potter goes back years earlier, to 1972, when he was acting in Theatre Passe Muraille’s seminal collective creation, The Farm Show, and she attended a performance in high school: “I remember thinking, ‘That guy’s very good!’”

At that point, a teenage McKenna was interested in acting but not necessarily as a career. Certainly, it wasn’t in her background. Her father, Sean McKenna, was born in Dublin and emigrated to Canada as a small child. Her mother, Bronislawa Tachynski — who later Anglicized her name to Betty Tash — was the daughter of Polish immigrants and raised on a farm in northern Manitoba. The two met in Toronto, where Seana was born in 1956. Sean was a self-employed businessman who ended up running a commercial paving company. Betty was a homemaker.

“They had nothing to do with the theatre,” McKenna said. “Although my mother did sing and was very vivacious, flamboyant, quite a stunning woman.”

McKenna, however, was drawn to the stage from an early age. As a preteen growing up in Etobicoke, she put on plays with the neighbourhood kids. Later, at high school in Port Credit, she fell under the spell of a dynamic young drama teacher, Bridget Harrison, who took her students on outings to Stratford and to that fateful Farm Show performance.

Still, when the time came for postsecondary studies, McKenna opted to enter the University of Toronto’s Trinity College as an honours English major. In the spring of her first year, on a lark, she auditioned for the National Theatre School (NTS) in Montreal at the urging of friends. When she received an acceptance letter, she was torn, but finally decided to defer her university scholarships and give it a try for one year. That one year turned into three — she graduated in 1979 — and she never looked back.

While still at NTS, McKenna was offered a position with the Stratford company by then-artistic director Robin Phillips. Surprisingly, she turned it down.

“I wanted to graduate,” she explained. “I hadn’t graduated from university, so I was determined to graduate from NTS.”

After leaving the school, she chose to spend her first few years in the profession doing new plays and collective work across Canada. She finally joined the festival in 1982 and made a big splash two seasons later as Juliet to Colm Feore’s Romeo. Over the decades, she’s tackled most of the major Shakespearean female roles, from Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Katherina in The Taming of the Shrew, to Cleopatra and Lady Macbeth. But she encountered the familiar frustration when she reached middle age and the parts in the canon become secondary. “To be able to combine your experience with a great role as you grow older is unusual for a woman,” McKenna said.

She and Potter came up with a solution when they pitched their Richard III to Stratford. Potter confessed he had some trepidation about whether McKenna could play the part, until she did an impromptu audition for him one morning at breakfast.

“She’d taken a shower, and she came out in a robe with her hair down over her face and spontaneously did this strange walk that scared the crap out of me,” Potter recalled with a chuckle. “She transformed in our dining room in front of my eyes, and if I had any doubts that she could pull it off, they were over.”

McKenna’s audacious performance was a festival landmark, kicking open the door for more gender-neutral and gender-swapped casting. She followed it with the title role in Julius Caesar in 2018 – playing the part as a man (critic Jamie Portman wrote that her performance “reache[d] into the very marrow of Caesar’s being”). Her steely, matriarchal Lear for Toronto’s Groundling Theatre Company that same year helped convince the late Stratford legend Martha Henry to put aside her reservations and essay a female Prospero in The Tempest.

These days, McKenna doesn’t have many roles left on her wish list. She’d be game to do Timon of Athens, playing either the misanthrope Timon or the cynic Apemantus. Apart from Shakespeare, she’s always wanted to play the gossip-mongering housewife Rose Ouimet in Michel Tremblay’s Canadian classic, Les Belles-Soeurs. She still remembers the play’s English-language premiere in Toronto in 1973, with the great Quebec actor Monique Mercure as Rose. That dream will finally come true this year at Stratford, when she’ll take on the part in a much-anticipated revival, which will also mark McKenna’s 30th season at the festival. “I have no expectations that I’ll live up to anything [Mercure} did,” she said. “I was so knocked out by her.”

Otherwise, she welcomes the unknown.

“I don’t want to have expectations,” she said. “I’m delighted by things that come my way.” Like her last show in Toronto, Kat Sandler’s witchy thriller Yaga, which premiered at the Tarragon Theatre in 2019. Or her current one, Things I Know to be True. Bovell’s script won her over from the get-go. “I was very moved by it,” she said. “It’s not often you read a play and you find yourself weeping, and you go, ‘That’s not even the climax of the play, why is it so affecting?’ He’s a wonderful writer.”

The production is being directed by Company Theatre artistic director Philip Riccio, with whom she’s never worked, and apart from McCamus, a fellow Stratford vet, and Christine Horne, who plays their oldest daughter, the cast is also new to her. It includes Alanna Bale, Michael Derworiz and Daniel Maslany. “There’s a huge age range” in the rehearsal hall, she said. “It keeps you on your toes.”

McKenna is particularly sympathetic to young actors – after all, her own son entered the profession. Callan decided to act without any outward encouragement from her and Potter, and like any parent, she has her concerns.

“It’s such a hard life, it’s full of rejection, and you worry about that,” she said.

“But at the same time, there are so many extraordinary things about being in the theatre that it makes it worthwhile.”

And if there’s anyone who knows how to bring the extraordinary into the theatre, it’s McKenna.

Seana starred in Things I Know to be True at the CAA Theatre in Toronto February 1–19, 2023.

Comments