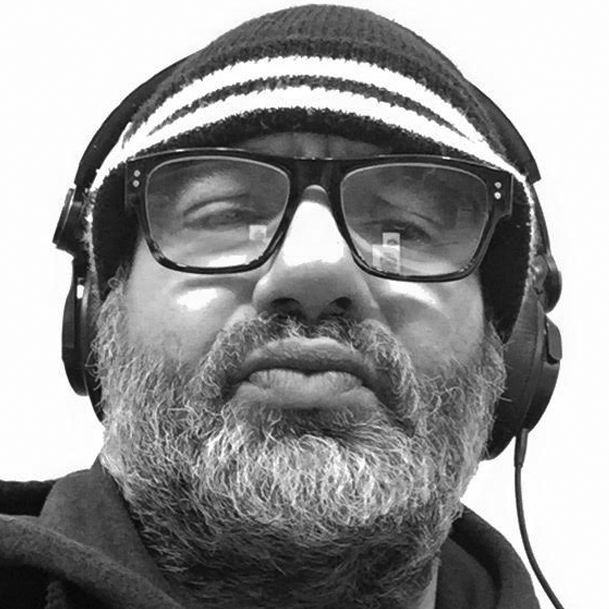

Spotlight: Kim Coates

Kim Coates is not afraid of failure. In fact, from the outside, it would seem that failure is afraid of him. At the very least, it seems to respectfully avoid him. But the boy who has done Saskatoon so proud can’t help but taunt failure every now and again just to keep things interesting. He is returning to the stage, after a twenty-seven-year absence, to tackle one of the most demanding roles written in the last twenty years: Johnny “Rooster” Byron in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem.

I first worked with Kim Coates—or Coatsey, as a lot of his friends call him—around 1986. It was quite brief, in some movie you’ve never seen, where I was credited as Husky Man. Husky Man was using a payphone (something you youngsters may have to Google) that Kim’s character wanted to use, and Kim either grabbed me and threw me out of the booth or put a gun to my head and told me to get lost, I honestly forget. That was my entire part. Maybe one or two lines. I didn’t have much to do with him on the day but I noted how electric and dynamic an actor he was and how excited everyone on set seemed to be that he was there. I knew he was a guy whose career I was going to keep an eye on and one I hoped I’d get to do some real scenes with one day.

So, who IS Kim Coates? Or rather, who WAS he before he became the Kim Coates we know now?

People see him and know him as Tig Trager, his Sons of Anarchy character: wild, violent, and unpredictable. Kim is not Tig.

Kim Coates (centre) in Neptune Theatre’s West Side Story. Photo courtesy of Kim Coates

First and foremost, Kim is a proud Canadian, even though he has lived in LA for the better part of the last three decades. He was a major part of the Canadian theatre landscape back in the ’80s, with a run of plays that started at the University of Saskatchewan. He acted with and was directed by his classmate Jim Guedo, who now runs the Theatre Arts Department at MacEwan University in Edmonton.

“Kimbo was always a Hollywood star,” says Guedo in a telephone interview. “The world just finally caught up to him.” He continues, “We did countless shows together, to the point where we really developed a shorthand. When I was directing a show he was in, I didn’t see myself so much as directing him as that I was a jockey who was riding a thoroughbred. I just let him run and would occasionally nudge him, shape him, harness him a bit.”

“No” is a word Kim isn’t afraid to use. In fact, I do an imitation of him that consists ONLY of saying the word “no” over and over and over, which he seems to get a real kick out of. I understand this side of him. The only power an actor ever has when trying to carve out a career for themselves is the power to say no. It is the hardest muscle for actors to develop because most just want to work. And most want to work in film and television as quickly as possible, where the pay is considerably higher than it is in theatre. So why didn’t Kim want to jump into it, like every single other actor on the entire planet starting out?

“I knew I was good. But I wanted to get good good,” Kim tells me. “I heard somewhere recently that film makes you famous. TV makes you rich. But the stage makes you good. And that’s absolutely true.”

He told Goddard that he wanted to work at the Tarragon and to audition for Shaw and Stratford. “It was ’82, ’83. I was waitering at the Nags Head Tavern, living with Diana, my now-wife. I was twenty-three years old and I got a call from Brian Richmond at the Magnus Theatre in Thunder Bay. Went and did Tartuffe and Of Mice and Men. Came back to Toronto and I did Equity showcases so people got to see who the fuck I was. And then my mentor, Tom Kerr, left the University of Saskatchewan and took over the Neptune Theatre in Halifax, and that was really the beginning of becoming the actor I am today.”

He did eleven plays at the Neptune. He knew he’d never wait another table in his life.

Joanne McIntyre and Kim Coates in Neptune Theatre’s Fool For Love. Photo courtesy of Kim Coates

In 1985 he got invited by John Neville to join the Stratford Festival’s Young Company, and he moved his life to Stratford. In his second year, he became the youngest Macbeth in the Festival’s history. The following year he returned to Toronto to do A Lie of the Mind at the Tarragon, then went to Saskatoon for Fool For Love.

Around this time word of Coates’s acting chops spread all the way to New York City, where he went and where he was cast. On Broadway. In A Streetcar Named Desire.

There was just one small hitch. They only wanted Kim to understudy Aidan Quinn, who would be playing Stanley and who was already well on the way to becoming a name. Kim absorbed the offer and politely refused it. Again with the fucking “no.” He’d already played Stanley in Halifax and had no interest in understudying anyone, on Broadway or not. The producer, Paul Levin, asked Kim if he could hang around New York for a couple of days while he tried to figure something out. Levin came back offering Kim a guarantee that if he would understudy the part, he would get a shot at the run on Broadway whenever Quinn left the show. “It was a four-month contract,” Kim recalls. “They weren’t sure when Aidan was going to leave the show. Could be a month, could be three and a half months. But whenever he did leave the show I would play the part.”

Kim agreed to the amended offer and, as fate would have it, during the final preview Quinn broke his collarbone in the shower scene. Quinn went on for opening in a sling but left six weeks later, and Kim stepped in and played the part for three months. He did Dracula in Atlanta after that and Les Liaisons Dangereuses in Louisville. And then a third run of Streetcar in 1990 at the Vancouver Playhouse. That was the last time he has ever been on a stage, until now.

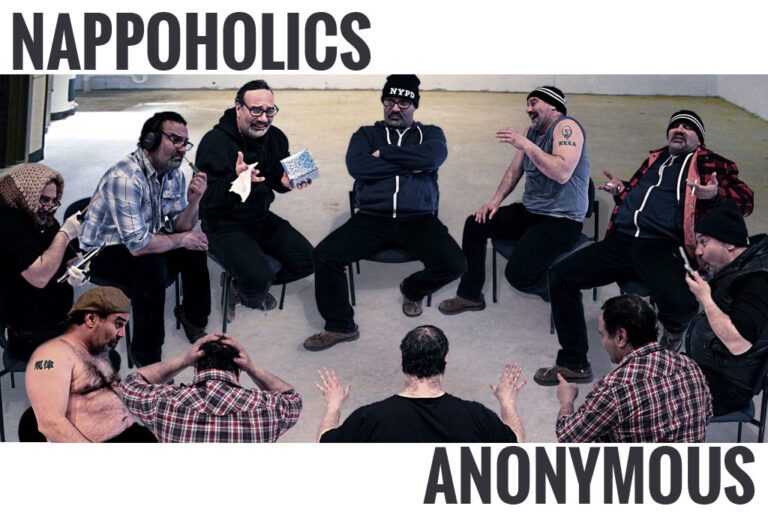

Kim Coates in Jerusalem. Photo by Dahlia Katz

* * *

The second time I worked with Kim, we did an episode of Earth: Final Conflict, which I have never seen and which I remember virtually nothing about. But I do remember spending a week constantly talking to Kim and picking his brain about theatre and acting and the move that he was about to make to the States.

“I always tell younger actors not to be in a hurry to get smothered in LA or get smothered in big centres when there is so much going on in Edmonton, in Thunder Bay, in Saskatoon. Take advantage of what your community has to offer first. Soak it all up like a sponge. Take your time. There’s so much going on [everywhere] now,” he advises. “Make sure you do that first. And then if you want to go, you can go. Because you do want to go where the best stuff is. Now, that can still be Thunder Bay. That can be New York. That can be Prague. But, ultimately, that is the goal, to go where the best stuff is.”

And that’s what he did. He booked his first major film audition for The Last Boy Scout and then went on to appear exclusively in feature films for years, such as The Client, Waterworld, Pearl Harbour, and Black Hawk Down. He was no longer doing any theatre or any television at all. “Didn’t want to,” he explains. Simple as that. Little did he know that television was where he would find the role that would, ultimately, make him a star.

“There were some really lean times. When those towers came down, the whole world changed. None of us worked for two years,” Kim says.

Kim Coates and Kevin Costner in Waterworld. Photo courtesy of Kim Coates

While Kim had decided against television, a little show called The Sopranos had come along and changed everything. Television went from being a second-class cousin of feature films to being a very fertile creative ground where longer stories could be told with all of the artistic standard usually reserved for cinema. Kim saw what was happening on cable and knew he had to start being smarter with how he steered his career.

In 2008, Sons of Anarchy landed on Kim’s desk. He read for Clay. Read for Bobby. Read for another part called Hawk that was never used. He didn’t get a part. About two months later, he was on the golf course without his phone on him; his phone is never on when he golfs. When he turned it back on, there were about eighteen messages waiting for him. Sons had decided they were going to re-shoot the pilot and re-cast the show. They needed a sergeant-at-arms. Kim went home, put on some jeans and cowboy boots, and went in to read for them. They offered him the role.

Before accepting the offer, Kim asked to see something more. “It was just so violent, so I said, ‘Not for me.’” Of course, he did. It wouldn’t be a Kim Coates story if he didn’t say “no” at some fucking point, would it?

But he and creator Kurt Sutter went on to talk character and plot lines and motorcycles until Kim could see himself in the role. By ten o’clock that night he had signed with the show and by five o’clock the next morning he was on his way to set. “Before Sons,” Kim tells me with legitimate humility, “I was always ‘that guy.’ That guy from this or that guy from that. Cut to seven years later, when Sons ended, and now I’m Kim Coates to my fans… The power of television. I had no idea.”

Kim Coates and cast members in Sons of Anarchy. Photo courtesy of Kim Coates

* * *

The third time I worked with Kim was just over a year ago. That wish I had on set the first time we worked together came true. I was one of the leads in the miniseries Bad Blood, which he starred in and co-produced, and for which he was just nominated for the best lead actor Canadian Screen Award. We saw each other and worked together, almost daily, over eight weeks in Montreal and Sudbury, and played in about seventy-five scenes together. No matter where we went, people always wanted Coatsey’s autograph, or a selfie, or just a shared moment of his time, which he always happily obliged.

Kim Coates has pretty much done it all at this point. He could rest on his laurels and keep picking and choosing television and film projects that he is interested in. So, why theatre? Why go back to where he started?

“Stage and only stage is that immediate non-stopping train that never leaves the tracks. In film we can call cut. We can say, ‘Let’s do it again,’” he says. “[But] I need to be challenged. I need that feeling of non-stop madness from beginning to end again.”

“I’ll tell you this about Kim,” says Guedo before signing off the phone call. “I remember reading a quote from Peter Sellers [the theatre director, not the actor]. He said, ‘If I read a play and it terrifies me, I have to do it.’ That’s Kim Coates.”

Producers Philip Riccio and Mitchell Cushman sent Kim exactly that with Jerusalem.

Kim Coates and Diana Donnelly in Jerusalem. Photo by Dahlia Katz

The first time he read it, Coates recalls, his response was: “Without a doubt, absolutely not.” (Big shock there.) “I didn’t understand [the play],” he says. “It was over my head. I didn’t give it my full attention at the time. The language was esoteric, a lot of local slang… and it was a monster part. Bigger than Macbeth, bigger than anything I’d ever done. So I said no.”

Riccio and Cushman asked him to read it again, so Kim did. And that second time, he gave it more attention, and he saw something there. But he was about to work in two different miniseries: Godless, a huge Netflix western, shooting in Santa Fe, and Bad Blood. So he said no again.

“But I really liked Philip and Mitchell, and they had contacted Butterworth’s lawyer and extended the option. Around this same time, I gave the play to my daughter Brenna [who will be playing Tanya in Jerusalem] and right away she called me and said, “Dad, you have to do this play.”

I ask Coatsey one final question, which I know will piss him off (and it does): “Why bother taking this risk? What if it doesn’t go well?”

“I took this part because it means I’m coming back to my first love. Rooster Byron is a daunting part but let’s be clear, none of it scares me. None of it. But somewhere inside of me my heart is beating at quite the excited pace.”

If I were failure, I’d be shitting my pants about now. Kim has never been more prepared or up for any challenge. And it doesn’t seem like he is doing it to prove anything to anyone at all. Not even himself. He is doing it because he is Kim Coates. And when Kim Coates wants to do something, he just does it. And if anyone or anything even thinks about getting in his way, they’re gonna end up like that poor clueless Husky Man in the phone booth.

Comments