Spotlight: Tom Rooney

“You talk some more,” Tom Rooney says over dinner at Queen Mother in Toronto. “I think this article should be about you. Your conversation with me.”

“Well,” I say. “It is, a bit.”

I first met Tom at the end of 2014 when we were starting rehearsals for The Seagull, directed by Chris Abraham. Earlier that year he’d won a Dora for his staggering work in Kristen Thomson’s Someone Else, and his performance as a doctor dealing with an unraveling marriage and a complicated relationship with a patient gutted me. So I began The Seagull feeling awed and intimidated by Tom. I was awkward and nervous around him, and I found it difficult to make eye contact for a good while. But given the roles we were playing—he was Trigorin, the successful writer, and I was Nina, the budding actress who falls disastrously in love with him—I think my discomfort was probably useful. Once I got over my initial starstruckedness, however, playing opposite him was a bona fide dream. “You’re my favourite,” I remember telling him after our opening performance. “Like, ever.” And that continues to be true.

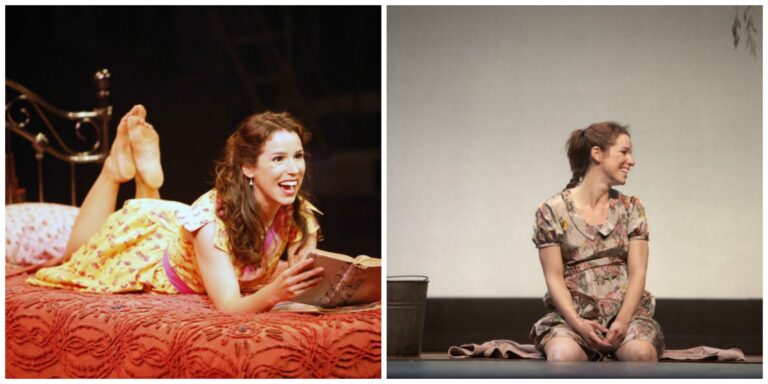

Christine Horne and Tom Rooney in The Seagull. Photo by Guntar Kravis.

I have to assume that I am not the only actor to consider Tom Rooney their favourite. He’s exceptionally skilled, of course, but he is also exceptionally present. He is exceptionally alive. Being on stage with Tom doesn’t feel like being on stage with anybody else. He cares so deeply about the play. He cares so deeply about the story.

I’d never spent as much time, through the course of a run, in such continuous dialogue with another actor about what we were doing up there. Is this moment still working? Is it clear? Should it be this instead? What if we try this? I felt like we were actively working together, every show, to further hone our scenes, our relationship. I can be fairly rigourous in my own work by myself, but I don’t think I’d ever felt such rigour in partnership with another actor before. It was thrilling and I savoured every second of it. I loved two-show days because it meant more of that. It meant more time on stage with Tom.

I’ve seen virtually every play he’s done since The Seagull, because as much as I love acting with Tom—and the list of plays I’d like to do with him is ever-growing—I also love watching his work from the audience. He is, consistently, the most interesting part of any production. When Tom steps on stage, the atmosphere in the theatre changes. It’s palpable. Ask anyone who recently saw The Wedding Party, or Breath of Kings. And it’s particularly acute when he’s doing Shakespeare, which, as he’s currently in his tenth season at the Stratford Festival, has made up a significant portion of his career. And though I haven’t had the chance to work with Tom on stage again since that first time, he was an invaluable resource, sounding board, and friend to me when I recently did my first Shakespeare play in quite some time, Prince Hamlet.

“Let’s just talk,” Tom says when we first sit down at Queen Mother. We’re both a little anxious, neither of us really sure where to start with this interview. But we order our drinks—a martini for him, a sauvignon blanc for me—and he begins.

Tom Rooney, centre, with Kristen Thomson and Jason Cadieux in The Wedding Party

Tom was born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, in 1964, and raised in Saskatoon. His father worked at the Federal Penitentiary, and his mother was a singer. Tom, along with his six older sisters, sang as well. “Singing was the easiest thing to me, ever,” he tells me. “And then I got a degree in voice [from the University of Saskatchewan] and it ruined me.” He worked with some great teachers, but he felt the need to “get it right,” and singing wasn’t as easy or enjoyable anymore. He compares the experience to what many others feel about going to theatre school: that being taught to do the thing can so often kill the freedom and joy that made us want to do the thing in the first place.

Tom found himself spending more time in the drama department than the music department and met his first big mentor there: Henry Woolf. “He went to high school with Pinter,” Tom says, “so we did a lot of Pinter.” (When I get home and look up Henry Woolf, I discover that beyond simply being high school friends with Pinter they were frequent professional collaborators, and Woolf was a fairly major player in the avant-garde theatre scene in 1960s England. Not a bad mentor to happen upon while you’re haunting the drama department.)

Tom’s first jobs out of school were musicals, but fearing he’d be pigeonholed as a musical theatre performer, he began to play down his musical side and did more and more straight theatre. The late 1980s were a particularly thriving time for Saskatoon’s theatre community (when I ask him why that was the case, he isn’t sure) and Tom quickly found himself in the middle of it. There was a great deal happening locally and a lot of exceptional artists were coming through from across the country.

One such artist was Robert Lepage, who had achieved tremendous success in Quebec by that point but wasn’t yet an international star. When Lepage was invited by Gordon McCall to work at Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan for his bilingual production Romeo and/et Juliette, Tom was cast as Romeo. “The good thing about Saskatoon was that it was a small community, and so there weren’t a lot of my types around—male ingénues who could also sing and dance well enough. If I had been in a bigger city, if I had been in Toronto, I would never have had those opportunities.”

Tom Rooney with Celine Bonnier in Romeo and Juliette, produced by Nightcap Productions’ Shakespeare On The Saskatchewan Festival.

He stayed in Saskatchewan until the mid-90s and then started travelling back and forth to various regional theatres. It was while working at Alberta Theatre Projects in 2000 that he was spotted by Marti Maraden, then the artistic director of the National Arts Centre. He was playing the Biographer in Michel Marc Bouchard’s Coronation Voyage.

“While I’m watching the play,” Marti remembers, “half of my brain is thinking, This is a part that would be very difficult for the average actor to bring to life in so many dimensions. But Tom was amazingly effective. I couldn’t keep my eyes off him.”

She tells me the other roles were more accessible to an audience, but the Biographer was a very enigmatic role without a clear back story. Tom met the challenge and was captivating. Intrigued, she got in touch with him and invited him to work with her at the NAC. After a couple of seasons there, in which he played Dr. Stockmann in An Enemy of the People and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, Marti said to him, “If you are ever going to play Hamlet, you have to do it now.” Tom was nearing forty and Marti felt his Hamlet window would soon start to close. When I ask her why it was she had thought Tom needed to play that part, she quotes Ophelia:

The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword;

The expectancy and rose of the fair state,

The glass of fashion and the mould of form,

The observed of all observers…

“Hamlet has to be all these things,” she continues, “and I knew Tom’s range as an actor was vast enough to encompass them. And above all I knew he had a great heart.” They tackled the play together at the NAC in 2004.

Marti feels there are only a few actors in any generation who can play Hamlet brilliantly, and for her Tom is one of them. “He is one of the most inventive and original actors I know. Each day in rehearsal he revealed a new facet of the character, and he never stopped discovering.” Her description of Tom’s performance—how he encompassed Hamlet’s private despair, for example, or his painful, distrustful love for Ophelia, or his boundless affection for the players—makes me wish more than anything that I had seen it.

“Tom was so generous with his fellow cast members but he also went into his dressing room and he closed that door and he was almost like a monk going into his cell,” Marti says. “Such a sense of devotion. He lived and breathed that role.”

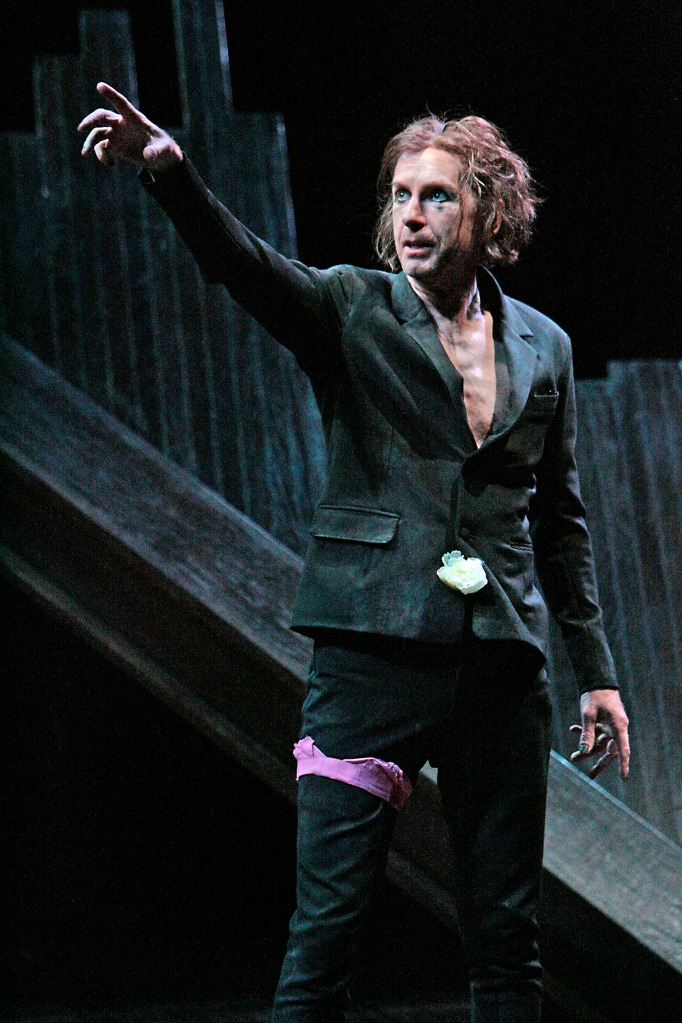

Tom Rooney as Tartuffe in Tartuffe. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Thirteen years later, and two years after we’d met on The Seagull, I was in rehearsals for Prince Hamlet, as Hamlet, with Why Not Theatre. I did not feel like one of the few actors of my generation who should be playing this part, particularly not when shockingly few women have been given the opportunity. (That there hadn’t been even a midsized Canadian production of Hamlet starring a woman by then was, frankly, bullshit. It’s 2017.)

I’d done only bits and pieces of Shakespeare over the past few years (my last real production was Romeo and Juliet in High Park in 2010) and I was feeling massively insecure. I was convinced that I hadn’t done enough Shakespeare to deserve this, or to be good enough for this. I hadn’t put in my time. Without even trying I could rattle off thirty women who should have played this part long before me. And on top of my feelings of Shakespearean inadequacy, I’d also recently given birth and was overwhelmed by just how much time I didn’t have to focus on this enormous job I was about to undertake. I’d spent the last months of my pregnancy propped up in front of my Lexicons, I learned all of my speeches while breastfeeding, and I was in an almost constant state of anxiety about how I was ever going to do this.

My go-to Hamlet helper was Tom. “Did you say sullied or solid?” I’d ask. Or, “All the reference books say I should pronounce it ca-NON-ized for the metre but I feel ridiculous saying that, what did you do?” Or, “We’re in tech and I still don’t understand the fucking nunnery scene.” And he would enthusiastically, generously talk through it with me, always leading me back to what was evident in the text. Some of his insights I outright stole, and others opened the door for me to make my own discoveries.

“When [you] have seen so many Hamlets and read so many Hamlets, you start rehearsals with so many ideas,” Tom says. “My analogy is, you walk into the big box store of Hamlet and there are shelves and shelves of essays and performances and you walk past them all and eventually you get to the very back and there’s this script. It’s dusty and it’s like, ‘Hey, what’s this? Let’s just read this.’ And it’s just the script, but it’s so hard to just hear it, see it. Given everything that we know, given everything that the audience knows, it takes work to get beyond all that and [just let] the script affect you.”

Hamlet or otherwise, for Tom the script is everything. He works on his text more than any actor I’ve ever met. “He’s relentless,” says Chris Abraham, artistic director of Crow’s Theatre and the director Tom has worked with the most in recent years. “I know that he goes home and works and wakes up and works. He is obsessed with figuring out his job in the dramatic machine.”

Tom agrees, “That’s what I love best. When I know what my job is in the story.”

Tom Rooney with Brigit Wilson, left, and Rod Beattie, right, in The School for Scandal. Photography by Cylla von Tiedemann.

At dinner we talk at some length about why we’re even doing this: Why do people want to be actors? What is it about human beings that we crave story? Why does every small town have a drama club? But none of my answers are enough for him. When I say it’s because it’s thrilling, because people want to be seen, he says “But why?” He is obsessively curious about theatre, and storytelling, and performance, and why so many of us are drawn to it.

“Did I tell you about my street performing phase?” he asks. I assure him he did not. “It was that thing everybody does after university. Go travelling and have an adventure.” Tom’s post-university adventure took him to Australia and New Zealand for two months, with a friend who was a juggler and street performer. The two of them paid their way performing a spontaneous thirty-minute street show in public places, drawing crowds of sometimes hundreds of people. “Because I wasn’t a very good juggler, there was a lot of padding. A lot of jokes and gags.” He tells me about one act that involved plate spinning and alternating passages from Nietzsche and a children’s book called I Am a Bunny.

“And these people,” he continues, “they’re downtown to shop, to do errands. They didn’t expect to see a show.” But by the end, every time, that group of strangers had all experienced something together, and they were suddenly a little community. They had something in common, out of the blue. “And I always remember that felt so pure,” he says. “I think that’s the accomplishment in theatre. You get a room of strangers together, tell them a story, and by the end of the night they know each other in some way, because they’ve had the same experience. And that’s kind of… that’s amazing.”

Tom joined the company of the Stratford Festival in 2008 when Marti took over artistic directorship with Don Shipley and Des McAnuff. “And I’ve been there ever since,” he says, smiling. Tom now lives in the town of Stratford with his partner, the brilliant and much sought-after designer Julie Fox.

Tom’s Festival resume is varied and impressive. From big musicals to Shakespeare, from broad comedy to dense tragedy, he has done it all. “He’s a real chameleon as a performer,” says Chris. “I sort of think there’s no part he can’t play.” Tom’s an incredible clown as well as being a fantastic dramatic actor, and he really understands and equally respects both comedy and tragedy. It’s why so many directors at the Festival clamour to work with him. Antoni Cimolino, Stratford’s current artistic director, says, “He’s one of the most versatile actors I know.”

[display_gallery]“As far as theatre in Canada,” Tom tells me, “[Stratford’s] an eight-month gig. They [program] great plays and they’ve been very good to me, giving me good, interesting, challenging parts. And what’s great about Stratford is you get to practise. You can work out with Shakespeare and exercise with that text in front of an audience for months and months and months, and it’s a great opportunity to get better at it. Not very many people get that, outside of Stratford, in Canada.”

And Stratford also provides actors the opportunity to revisit the same play over and over. Sometimes that means another shot at a part they’ve already played, and other times it’s exploring the same play from inside a different role. “With those big plays, with Shakespeare, it’s an endless riddle. There’s always something new that you haven’t heard before, haven’t seen before, haven’t realized before. It’s so dense that it’s impossible to get it all, ever. And the more experienced you are—not only the more times you’ve done the play but the more experience you’ve had with classics and with Shakespeare—the more tools and the more muscle you have to work on it. Stratford gives you that opportunity.”

“Let’s talk about Hamlet,” he says, turning the interview around on me not for the first time during our dinner. “What did you like about playing Hamlet?” I tell him that, as a woman, it was great to be able to do Shakespeare and to think and talk about things other than the men. Because so many of the roles for women, I say, even the major ones, are about what men are thinking and feeling and doing. I could never understand the notion that “there is no subtext in Shakespeare.” I always thought, That’s impossible, there has to be more. I have to be thinking about more than this. But with these big male roles, with Hamlet, I can understand that idea. Because there’s no room to think about anything except what I’m saying. So it was a very rare opportunity, I tell him, to have so much to think and say and feel and do.

“We talk about practise… I’ve been very, very lucky because I’m a guy,” he says. “I’m a white guy. And I’ve been able to practise because every story is basically about me. There have always been opportunities for me to practise. Which is not so for anybody else in this business.”

One of the ways Tom acknowledges this imbalance is with Gina’s Prize. Named for his late partner, the Gina Wilkinson Prize is awarded to an emerging female director, specifically one transitioning into directing from another career in the theatre. It’s a $5000 award given out annually on March 10, Gina’s birthday.

Gina was an actor for twenty years, and Tom tells me that in any new-play workshop, she was “always, always the smartest person in the room. She had a great eye and ear for story and how it worked and how it should work. So she always had the director in her blood.” She began directing when she was in her late thirties, with jobs at Alberta Theatre Projects and the Shaw Festival. When she passed away in 2010 at age fifty, Tom and a committee of Gina’s friends and colleagues created this award to keep her name alive. “She was a part of many different communities across the country. I thought her name should be kept in the theatre. In those theatres.”

As our conversation winds down I ask him if there’s anything else he wants to talk about, and he tries to articulate for me how he feels about his job as an actor. “These days, in this social and political climate, the truth is less important than what one believes. I think to do my job well, so that it has impact and affects people, it’s more important than ever to be truthful and honest on stage. So that people, audiences, not only see and hear the truth but feel the truth, to be reminded of what truth feels like.

“So I think when it actually works, when I’m doing the job I’m supposed to be doing—I feel like this is so obvious, it’s embarrassing—but I’m actually bringing my own self. In an incredibly honest, unflinching kind of way.”

That’s what I liked about Hamlet, I tell him. I felt like I could only be myself. I was as close to being me on stage as I think I’ve ever been able to be. “There’s something about that part that can’t be anything but that,” he says. “Because it’s so personal.”

Marti tells me, “I said to him once, ‘Tom, you are incapable of lying on stage.’ He simply can’t do something false.” And I really believe that she’s right. Tom brings his true self to the stage—to his work—with rare integrity, clarity, simplicity, and courage. He is the best Hamlet I never saw.

Correction: We incorrectly credited the wrong photographer for the picture of Christine Horne and Tom Rooney in The Seagull. The photo was taken by Guntar Kravis. Intermission regrets the error.

Comments