What I Wish I’d Known: Augusto Bitter

In What I Wish I’d Known, Graham Isador asks theatre artists what advice they’d give younger versions of themselves. The question is a jumping off point for larger conversations about the artist’s work.

A few months back I spoke with Augusto Bitter for a VICE piece. The framing of the article talked about the childhood moments that shaped people the most. Bitter shared his immigration story from Venezuela to Canada, explaining how the blacklisting of his parents by Hugo Chávez amongst the backdrop of political upheaval lead to their exit. In the interview he spoke with candour and passion, riffing on the complicated nature of his love for both his childhood home and the great white north, and how both those things play into his identity as a queer male. It was a great chat. I felt like I learned a lot.

Bitter brings that same open energy to each one of his performances, which has got to be one the reasons he keeps getting booked for roles. Just a couple years removed from theatre school the performer has been consistently working, with notable performances in Lear at the Harbourfront Centre and The Monument at Factory Theatre. Those shows have earned him attention from the media. He’s been consistently named as an artist to watch. People seem to be paying attention to what he does.

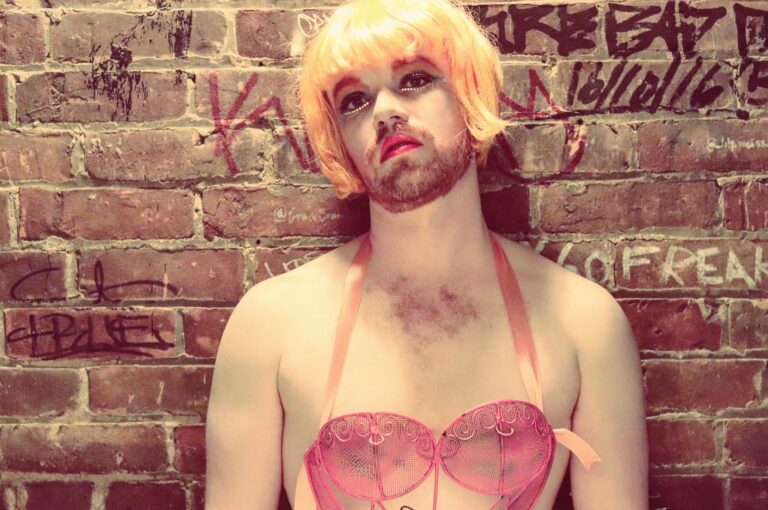

What he’s doing next is a solo show. In CHICHO the titular character, an ashamed-queer-Catholic-man-boy from Venezuela, attempts to feel beautiful despite his warring identity politics. Bitter has been developing the play over the past few years with Aluna Theatre, Pencil Kit Productions, and Theatre Passe Muraille. The subject matter has always been a labour of love for the performer, but has taken on particular meaning with the recent political situation in Venezuela. I’ve been working with the performer and his team on CHICHO. Recently we had the chance to talk about achieving success at a young age, hustling for your work, and what he’d tell himself as a kid first coming to Canada. You can read our conversation below:

Graham Isador: It’s not a thing I can say for a lot of actors, but for as as long as I’ve known you you’ve been a person that has worked. What’s it like to achieve success this early? Is the success something you’re aware of?

Augusto Bitter: It’s wild! I’ve definitely cried dramatically on my bike about it. I was raised in an extremely hard-working, selfless family that taught me to keep my head down and work. They were always very proud of me when I did get some sort of success growing up, but I still have no concept of how to “feel myself” and receive recognition gracefully. I get shy about my success, not wanting to ever seem like I’m bragging, backfiring to the point where I forget to pause and actually celebrate the little wins. This is compounded by always planning five steps ahead so I always have something to say when someone asks me, “What’re you workin’ on?” (Gross.) That slow, creeping kind of anxiety seeps in sometimes. The kind that tells me to constantly out-do myself and all my peers to stay “relevant”. So I’m practicing a lot of gratitude and grounding myself in concrete moments of joy to try and stay present.

What would you attribute the success to?

I’ve hustled. Very hard. I got good at writing emails and meeting people in person. I stayed in touch with previous instructors and mentors. I diversified my art practice by dabbling in different disciplines. I tried to see as much international theatre as possible. I can’t deny my parents’ financial support through post-secondary, which allowed me to have more time for non-paying gigs, networking, and writing. Creating my own work also gave me access to the capital-A “Artist” marker, which has a different scent that many young actors unfortunately get cheated out of. Most of what I’ve booked has been from auditioning like everyone else, but many have now also been referrals and offers. So, be kind to everyone. Including yourself. For real.

Is acting something you always expected to do?

Nope. I thought I was gonna be a chef, or a dentist. Something to do with mouths, apparently. Anything but a (petrochemical) engineer. I did always take class presentations far too seriously, and my first career was a Little B(r)other. I am very, very good at being loud and drawing attention. I’ve had to temper this, of course, ‘cause it’s annoying, and working for a laugh almost never gets you the laugh. Thankfully, the communities and ensembles I’ve been a part of have encouraged me and helped me find a balance. I am continuously finding my people.

Your family came over to Canada when you were pretty young. Were they supportive of you going into the arts?

I’ve always said I felt like I had to come out twice to my parents: first as an artist, then as gay. (I can’t wait to fabulously come out of my “emerging artist” cocoon, too!) Going professionally into the arts is not something any immigrant parent is likely to encourage their kid to do: “We sacrificed everything to come to this country… and you’re going to willingly choose to be a broke artist…?” It’s become clear to me that the only reason I’m a professional artist today is precisely because my parents made that huge, brave sacrifice. It wouldn’t have been an option in my family if we stayed in Venezuela, and even less with the living conditions now. My knee-jerk reaction is to say “no, they were not supportive” because they were (very) hesitant, but that is false. We agreed I could move to Toronto on the condition I would study a double major and so have a “fallback”. I’m apparently a sado-masochist and chose commerce as my other major. A year in, I was miserable, money was tight, and I was starting to get some momentum and meeting interesting people that made it seem possible to have a fruitful career. And then it just got… fruitier from there.

Some of that story plays into the larger themes in your new show CHICHO. Can you talk to me about the decision to make the piece and how it has evolved?

I knew I wanted to write for my strengths as a performer. Through multiple amazing chats with my friend and dramaturge Jiv Parasram, it became clear that it was a bit of a collage of many contradicting identities. I needed a through-line and I knew it had something to do with Venezuela and drawing attention to it somehow. It felt like a waste of creative energy if I didn’t do something meaningful with my privilege. I also knew I wanted to explore the form of a solo show—the first Canadian plays I read were Daniel MacIvor’s. The delicious challenge of a single performer transforming and holding an audience’s attention still feels like magic to me. Since then, I’ve trained with many different people that have expanded my rigour and my expectation of what theatre can be. I’ve dug deeper into my ancestry and indigeneity through the years. It’s all made the show weirder, sharper, and sillier.

Has the current political situation Venezuela changed the perspective on your show?

Absolutely. When we experimented this show a year ago in TPM’s BUZZ series, virtually “no one” knew what was happening in Venezuela. They were shocked. People would ask me on the bus: “Oh, do you go back home a lot?” … “Uh… no?” Many Venezuelans, on the other hand, said, “You missed this part!” or, “Why aren’t you talking about this?” So, how do you expose the horror of it better than a Google search could? We approach the crisis from a personal witnessing instead. A really productive dramaturgical opportunity arose by paralleling my own conflicting identities and the country’s conflicting history; they’re both impossible to explain in simple terms. Leading up to the show this time around, after the specific events of the last two months, people have come up to me saying, “Wow! Such good timing, huh?” It’s a bizarre feeling hearing strangers dissect your country on podcasts and news rooms everywhere. It’s forced me to think about nationalism, privilege, accountability, and ambiguity.

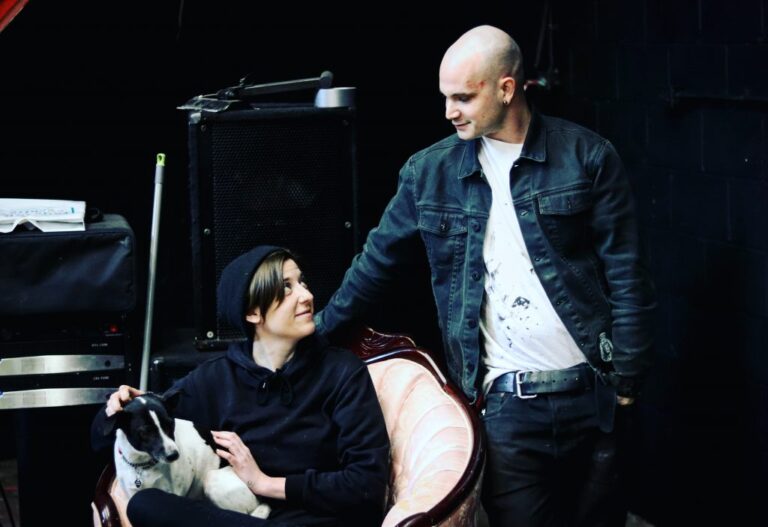

Photo of Augusto Bitter by Graham Isador

I’ve tried to stay up to date with the situation but fall behind pretty quickly. Why do you think other people have been ignorant to what has gone on in Venezuela?

It’s the same reason we hear very little about any atrocities in the “Global South”. I am “guilty” of falling behind too. Part of why no one knew/knows about Venezuela is because North America (and the English language) has made itself into the centre of the universe. Global media has never necessarily been as vocal about “intervening” as it has recently. We must remember that the current regime (this Bolivarian Revolution started by Hugo Chávez back in 1998) has been in power for twenty years and counting. It is an extremely advanced, manipulative dictatorship with terrible economic policies and widespread media censorship. It has been responsible for the death of thousands for almost my entire life. It is impossible for me to separate this emergency from my definition of what it means to be Venezuelan. I hope more than anything that we focus on the human. From the privilege of our full bellies, so much attention gets thrown to ideology and social-justice that we can easily forget people are still starving, people are still dying. You can donate to two different campaigns from our production partner Venezolanos Por La Vida here.

If you could tell your childhood self coming to this country about what you’re doing now how do you think they’d react?

First, he’d probably be shocked about my rapidly escaping hairline and throw out the hair gel. Then he’d smile really obnoxiously and be like: “You do WHAT? AND you get PAID for it?! And papi y mami LET YOU?!” He’d look forward to wearing pretty dresses and nail polish and honouring his queer ancestors. He’ll be relieved to see he went to an orthodontist eventually. He’d be sad to find out the crisis only got worse. He’d probably give me a long hug and go back to playing with legos.

CHICHO runs March 7th-24th at Theatre Passe Muraille. Details can be found here.

Comments