What I Wish I’d Known: Johnnie Walker

In What I Wish I’d Known, Graham Isador asks theatre artists what advice they’d give younger versions of themselves. The question is a jumping off point for larger conversations about the artist’s work.

I first met Johnnie Walker at a bar seven years ago. Walker and frequent collaborator/superstar Morgan Norwich were drinking casually with a friend of mine after selling out several shows at the Toronto Fringe. Fresh out of theatre school I admit that I felt a little starstruck. The two had made a name for themselves on the back of several stellar shows with their company Nobody’s Business. I had seen their work and loved it. The two had a playful energy that bolted between belly laughs and gut punching realness. They knew how to be crass and to be serious. They had earned great reviews and appeared on the cover of NOW Magazine.

It was my first brush with people in the theatre community who actually seemed to be making it and I spent the night buying rounds while trying to soak up some advice on how the duo had done so well. That night I learned two things. Both Walker and Norwich were only a couple of years my senior and found my googly ideas towards them cute, if a little silly. I also learned that the way they had gotten to make things was by just going out there and . . . well . . . making them.

Over almost a decade of knowing Walker, I’ve watched my friend carve out space for himself as a leader in Toronto’s queer community. Sometimes that means putting on amazing stage shows. Other times it’s hosting incredible viewing parties and drag nights. Often it’s throwing one of the best dance parties in the city. The hustle that goes into Walker’s work—whatever it is—is still something I admire all these years later.

Recently I had the chance to talk to Walker ahead of his latest show Shove it Down My Throat happening at Buddies in Bad Times at the end of March. You can read our conversation below.

Graham Isador: The first time I became aware of you was with your hit Redheaded Stepchild. Can you talk to me about the creation of that piece and how it felt to make something so well received?

I started writing Redheaded Stepchild at the tail end of 2009, so almost ten years ago. Wow! It’s hard to put myself back in the headspace of creating the show. I know I was very inspired by people like Daniel MacIvor, Kristen Thompson, Karen Hines—artists with elegant, masterful solo shows. I wrote a good chunk of the first draft at a master class Daniel MacIvor was leading at Banff, followed by many sessions of studio explorations and rehearsals with my “art wife” Morgan Norwich. It was a way to name and reckon with the strangeness of growing up with shockingly red hair, to give my inner child a big hug, and to make something fun to create, fun to perform, and fun to watch. Also, solo shows are very practical (he said while deep in rehearsal on a two-act, cast-of-seven behemoth)!

The reception of the show—and its longevity—have been such a gift. I’ve had teens wait for me outside the theatre in tears after seeing it. It’s such a personal and vulnerable performance for me to do, so the fact that it’s connected with folks the way it has has been a joy.

The show went on to tour and got rave reviews in various cities. It sold out crowds and charmed a lot of people. But afterwards—and I don’t mean this disrespectfully because it’s also true of my work—it didn’t lead to immediate job offers in theatre/programming in a season. Can you talk to me about how having a hit festival show doesn’t guarantee anything?

Oof, we aren’t pulling any punches in this one, huh? I guess you’re not wrong. If I think back to the initial high of doing Redheaded for the first time and getting five-star reviews and sold-out runs and having people say to me “Oh, this will lead to this, it will lead to that . . . ” Were there places I dreamed it might take me that it didn’t? Absolutely. But it did take me across the country. I’ve performed Redheaded Stepchild on and off from 2010 to as recently as 2017. It’s been seen by thousands of people, acquired more stellar review quotes than I can tastefully fit on a poster, and it was published a couple years back. It would feel churlish to complain!

So, no, a festival hit doesn’t guarantee anything—nothing does. Nothing is guaranteed. And when I think of the worst art I’ve seen by artists I admire, it’s the work they’ve made when they were under the impression success was guaranteed; when they were too comfortable. If you’re making art without even the tiniest ember of fear and doubt in your heart, I think there’s a very good chance you have nothing important to say.

Is there anything you wish you could tell the younger version of yourself during that time? Any advice you’d give?

I know this is the whole premise of your column, but I kinda hate this question! It’s so alluring to fantasize about those parallel dimensions where we made a slightly different choice in our early twenties and everything turned out so much better. But I can only live in this dimension. (And if we’re talking specifically about me not getting certain job offers or opportunities, maybe it would make more sense to advise the younger versions of other people to hire me more!)

But, if I must . . .

I suppose I would tell him to start touring sooner. To not be afraid to get out of Toronto, because he is going to cut his teeth as a performer on the Fringe circuit and see all this amazing art, make wonderful friendships, and find a real sense of community. Actually, I’m finding it difficult to think of advice that isn’t “do the things that I did anyway, only faster,” which is funny, because one of the things I grapple with in Shove It Down My Throat is the idea of hesitation. My natural propensity to hesitate often drives me insane, but how do you find the balance between hyper-caution and recklessness? So maybe the real best advice would be: you’re going in the right direction, even if the journey winds up taking longer than you planned for.

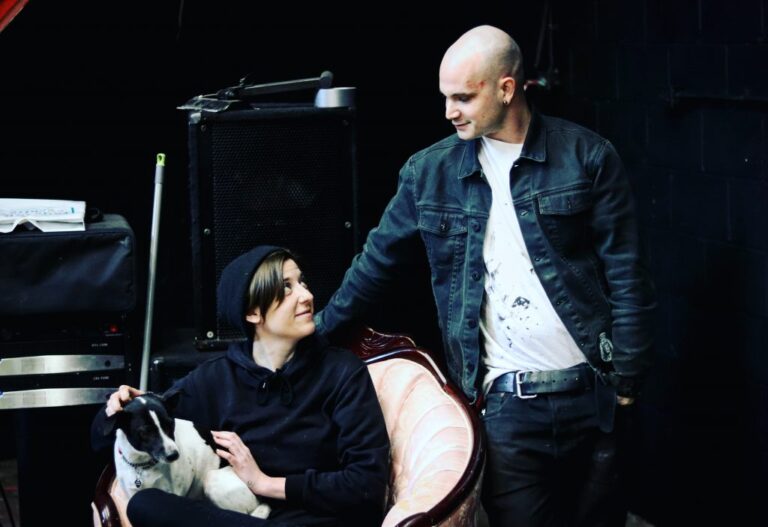

Johnnie Walker / Photo by Graham Isador

I’ve always admired the various hustles you’ve kept going between your work as a DJ/writer/director/performer/creator. Can you talk to me about how making a living in the arts means working a lot of different gigs?

The truth is, I’ve always been bad at day jobs. I spent a bunch of my twenties working in offices, but I never felt invested in what I was doing. It was like I knew they weren’t my real life, so I had a hard time taking them seriously. Becoming a DJ was a complete accident—a friend was under the mistaken impression that I was one already and offered me a monthly dance party at The Beaver. I said yes and then went home and googled “how to be a DJ.” Becoming a burlesque MC was also an accident. It’s all been very unplanned! I feel very fortunate to have been able to cobble together a living doing things are all objectively fun. And there’s a thread that runs through all these things. Whether I’m working on a play, or introducing a performer at a Drag Race viewing party, or telling corny jokes to kill time while strippers get changed backstage, or even queueing up the song someone’s drunk uncle just demanded at a wedding I’m DJing, I’m inviting people to help me build spaces where we can all come together and laugh or cry or dance or flirt or just celebrate. And it’s all creative, so for me, it all scratches that itch.

Shove it Down My Throat is happening at Buddies in Bad Times later this month. Talk to me about this show and your desire to return to work centered around you?

I’ve performed in about fifty percent of the plays I’ve written. To a certain extent, it’s just casting—sometimes there’s a part for me and sometimes there isn’t. There are times when I’ve felt a bit invisible with shows that I’ve written but haven’t performed in, and I think for me there is a desire to be like “Hey! Here I am! Don’t forget that this is my show!” With Shove It Down My Throat, my earliest impulse was just to write a show about Luke O’Donovan and I wasn’t necessarily sure whether or not I would perform in it. But very, very quickly it became clear to me that the show was also about me, about the journey I took to create the show, and about how Luke’s story affected me on a very personal level. It didn’t seem appropriate to have any level of detachment for this project; I wanted to be on stage, doing my best to tell this story, allowing myself to be fully implicated any time that story goes off the rails. It’s scary stuff!

How does it feel to be programmed as a part of Buddies 40th? How do you think your younger self would have reacted to that programming?

It feels amazing! I’m very proud to be a part of the 40th anniversary season, I’m so grateful for the support and mentorship Buddies has provided for this project, and in fact, Buddies has basically become a character in the show.

And here’s the deal with my younger self: he actually wrote the first version of Redheaded Stepchild as part of an application for what Buddies then called their Young Creators Unit. And he didn’t get in. And he was devastated. But he wasn’t defeated. And through the process of creating that show, he created himself. In the way that all artists, but especially performers, create themselves. Over and over again. Slowly and painfully. And he never would have dreamed of writing and performing a play like Shove It Down My Throat. It would have scared the shit out of him! But while he might not have known where he was going, he kicked off the journey that brought me here. So, perhaps my final words to him would be: thanks for getting the ball rolling, babe!

Comments